Carol and I cruised out to Manitou Springs last night to pick up our friends David Beers and Terry Blair, and we all went downtown to the Pikes Peak Center to take in the Colorado Springs Philharmonic‘s last concert of the season. On the program were Wagner’s Prelude from Die Meistersinger, Mozart’s Symphony #40, and Rimsky Korsakov’s Scheherazade. It had been way too long since we’d heard live music of any kind, and it was about damned time.

I was familiar with all three pieces, though I doubt I’ve listened to any least scrap of Die Meistersinger since Dr. Raymond Wilding-White‘s courses in college. Opera isn’t a big thing with me, and Wagner never takes ten minutes when fifty will do. Mozart? What can I say? Reliable and familiar, and great stuff when you want a graceful background for good conversation. But Scheherazade, wow. Conductor Lawrence Leighton Smith gave it all he got, and it was one of the most amazing classical performances I’d ever experienced.

It’s a stunning piece to begin with, an interweaving of a dozen or so Russian-ish themes with enormous energy and a loose program following the old tale of the 1001 Arabian Nights. Smith and the orchestra put their backs into it, and I found myself sitting on the edge of my seat in concentration. It was one of the few live performances I can recall which was better than the recordings in my own collection. I know the piece very well, and I found myself waiting anxiously to see how well they would do a particular passage. In every single case, it was well indeed–and by the end of the concert (it was the final item) I was exhausted. The temptation to treat music as background for other activities is strong, but when you’re paying thirty bucks for the seat, you pay attention. That may be the biggest single upside to live music heard in concert: It’s you and the music, nose to nose. We forget that at our peril.

Scheherazade and I have an interesting history. When I was 7 we got a very early stereo record player, and not long after that, my mother started bringing home a classical LP every month from the local A&P food store in Edison Park. (The remarkably durable independent Happy Foods is in the building now, and has been since the 70s.) I don’t precisely recall the deal, but I think they were a dollar if you bought ten dollars’ worth of food. My mother played the records a lot, hoping to instill a love of classical music in Gretchen and myself. It worked, at least until the first sparks of the British Invasion (not the Beatles–Chad & Jeremy) drew me to pop music in 1963. However, by that time I had heard six or eight well-known classical pieces dozens of times, including Scheherazade. I assumed at first that Rimsky & Korsakov were a duet of some kind, but hell, I was 8. (I’m not sure I even knew that there were detailed jacket notes inside the cardboard sleeves until I was well into my teens.)

The Colorado Springs Philharmonic concerts begin with an optional half-hour lecture given by the conductor, asssisted by the concertmaster and sometimes other members of the orchestra. Smith is a good presenter, and explained how the Great Russians took simple Russian folk music and made it into orchestral battleships like Scheherezade. He spoke of The Five, and reminded me of something that I’ve never entirely understood: Why don’t we ever heard the music of Cesar Cui and Mily Balakirev? I went through the classical side of my CD case and didn’t find a single piece by either composer, peppered as it is by Borodin, Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, and several other famous Russians. Their contribution may have been organizational (Balakirev did a lot to point them in the right direction and keep them all focused) but I’ll have to go looking for some of their work.

Hearing Scheherazade, Night on Bald Mountain, the William Tell Overture, and the several other pieces in the grocery store music collection made the back of my 8-year-old head just go wild with images and crazy ideas. It may not be far from the truth that classical music pushed me over the edge into writing fiction. Even today, when I need to crack a plot problem, I stick an upbeat classical CD into the player and crank it up loud. Eight times out of ten, the plot problem is toast, and the story continues. Music is good that way. I need to do more of it.

We’re going to see just how fat our pipes are tomorrow, when Canonical cranks open the spigot for Ubuntu 10.04 Lucid Lynx. It’s an LTS release, and I’m guessing that a lot more people will be grabbing it than usual. I may download it just to see how well the torrent works on Day One; in fact, I have a new hard drive on the shelf for my SX270 here and if abundant time presents itself this week (possible) I may swap in the new drive and install the release. This is the second-to-last machine I have that still uses the System Commander bootloader app, and I’d really much rather have grub everywhere.

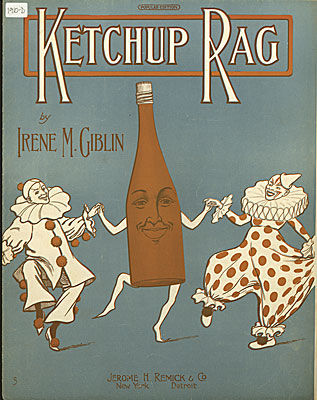

We’re going to see just how fat our pipes are tomorrow, when Canonical cranks open the spigot for Ubuntu 10.04 Lucid Lynx. It’s an LTS release, and I’m guessing that a lot more people will be grabbing it than usual. I may download it just to see how well the torrent works on Day One; in fact, I have a new hard drive on the shelf for my SX270 here and if abundant time presents itself this week (possible) I may swap in the new drive and install the release. This is the second-to-last machine I have that still uses the System Commander bootloader app, and I’d really much rather have grub everywhere. We had dinner with the family the other night at Portillo’s in Crystal Lake, and whenever we eat at a place like that, I wander around gaping at what I call “junkwalls”–old stuff tacked to the wallboard to make the place look atmospheric and (in this case) 1925-ish. Close to our table was a framed piece of sheet music for a song called “Ketchup Rag.” It was published in 1910 and is now in the public domain, and

We had dinner with the family the other night at Portillo’s in Crystal Lake, and whenever we eat at a place like that, I wander around gaping at what I call “junkwalls”–old stuff tacked to the wallboard to make the place look atmospheric and (in this case) 1925-ish. Close to our table was a framed piece of sheet music for a song called “Ketchup Rag.” It was published in 1910 and is now in the public domain, and  terms. I kept flipping into a wonderful DK book called The Visual Dictionary of Buildings to clarify certain elements of church architecture. Now that book I recommend, especially if you’re a writer trying to set a scene in a complicated building and aren’t entirely sure what an oculus is. (Or—quick, now!—define a “spandrel”.) There are some factual errors in Basilica, one of the worst of which suggests that poured concrete was used in some places in St. Peter’s. Not so—poured concrete was an ancient technology that was lost after Imperial Rome came apart and was not recovered until the 19th Century, or pretty close to it. St. Peter’s was built almost entirely of mortared masonry and sculpted stone.

terms. I kept flipping into a wonderful DK book called The Visual Dictionary of Buildings to clarify certain elements of church architecture. Now that book I recommend, especially if you’re a writer trying to set a scene in a complicated building and aren’t entirely sure what an oculus is. (Or—quick, now!—define a “spandrel”.) There are some factual errors in Basilica, one of the worst of which suggests that poured concrete was used in some places in St. Peter’s. Not so—poured concrete was an ancient technology that was lost after Imperial Rome came apart and was not recovered until the 19th Century, or pretty close to it. St. Peter’s was built almost entirely of mortared masonry and sculpted stone.