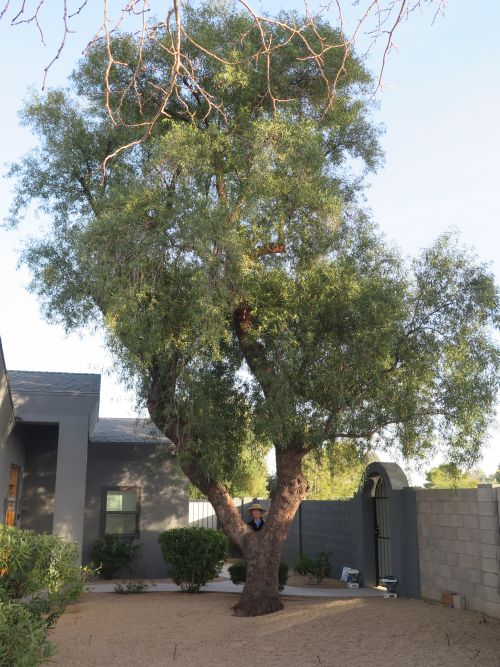

We had the big sumac tree by the front door cut down this morning. “Big” is no exaggeration, either: It was forty feet high, and two feet thick at the ground. (Look carefully and see Carol standing behind it.) It was a bad place for a tree that size, for several reasons. It was messy, and dropped seeds and leaves almost continuously between April and August. That was annoying, but what worried me was triggered by what happened to the guy right next door to the east of us: He had a biggish (but not even that big) mesquite tree snap in half in a windstorm and destroy the pergola over his back patio. I looked at the sumac and calculated what would happen if it lost structural integrity in any direction. If it fell to the west (toward me in the photo) well, ok. Any other direction, and it would take out one or both of two gates, part of our block wall, some or most of the guest room, and some or most of the front entrance, including our stained-glass encrusted front door.

That was a thick tree, probably as old as the original house, which is now 52 years. Some parts of the two main trunks were well over a foot thick, up higher than our roof line. I agonized over the decision, because it was a healthy tree that looked solid as a rock. But it was too close to the house, and even closer to the front gate. So we had a landscape company we knew and trusted come out and take it down. We also had them take down a much smaller mulberry tree that was not healthy. “Not healthy” is putting it mildly. See the photo of the mulberry’s main trunk, below.

Well, that had certainly been the right call.

The mulberry was quick; they had it down in twenty minutes. The sumac took the rest of the morning. The crew knew very well what was at stake, so it probably took more time than it might have, had it been growing in the middle of the back yard. It came down a chunk at a time, with each chunk tied on a stout rope and steered expertly down to terra firma. Some of the chunks were impressive.

Down, down, down. Then: Six or seven feet above the base of the trunk, the cross-section started to change. Take a look:

Egad. The damned thing was hollower than the sickly mulberry. After I took this shot, I dug into the chocolate-colored stuff surrounding the void and tore huge chunks out with my fingernails. There were probably three inches of actual wood–sometimes less–forming a 15″ trunk. I wanted to yell into the hole: “Hey, any elves in there? The chipper’s at the curb. Last chance to come out, guys. Bring cookies.”

Any regrets we had taking down the tree vanished the instant we saw this. Sure, there was solid wood all the way around. But consider the lever-arm torque on the tree trunk if a really bad west wind hit the tree’s canopy. Crunch! We could have been out our front entranceway.

There’s a downside to losing that tree: It provided considerable shade to the house in the worst of the summer. My electric bills are probably going to go up.

The major lesson in all this is that we assume trees are immortal, but they’re not. Trees live for some period of time, and then they die. The typical lifespan of a sumac like ours is 30-50 years. We were already past that. The rot at its core was nothing worse than old age. I remember when I was a kid, and the cottonwood trees in the parkway on Clarence Avenue all started to die at once. The city had planted them, six to a block on both sides of the streets, when they platted the neighborhood in 1929. But once the market crashed, nobody wanted to build homes there until the last of the 1940s, when the trees were already twenty years old. By 1960, the cottonwoods were over thirty years old, which is pretty much end-of-life for that species of tree. Just about every one was hollow enough to hold a whole bakery’s worth of elves, including a few really fat ones. My sister remembers that one of them on another street fell on a house and did some serious damage, and since the parkways belonged to the city, wham! Hundreds of cottonwoods vanished in a couple of years.

A postscript: Our cottonwood was the last one on the street to go. When we saw the logs stacked up, we realized that it was solid to the core. So trees have bell curves too. Bummer.

Anyway. We have plenty of other trees, none of them (thankfully) quite that close to the house. We have a gorgeous Aleppo pine in the front yard, outside the wall, that may exceed fifty feet high. Google tells me Aleppo pines typically live for 150 years. If I ever feel the need to hug a tree, well, I’m going with that one.