Well, the bookshelves got themseves full, and I still had three boxes to empty. So once again (I don’t know how many times I’ve done this!) I emptied piles of books onto the floor and flipped through them, in part for charge slips used as bookmarks, and in part to decide what books just had to go. Found a lot of charge slips, business cards, promo bookmarks, and other odd (flat) things tucked between the pages, including a small piece of brass shim stock. I built a pile of discards that turned out to be bigger than I expected.

One thing that went were my Scary Mary books.

Twenty years ago, I was very interested in Marian apparitions, and did some significant research. There’s a lot more to Marian apparitions than Fatima and Lourdes. The Roman Catholic Church approves only a tiny handful of apparitions. The rest don’t get a lot of press, and for good reason: The bulk of them are batshit nuts. The reason I was so interested is pretty simple: Perhaps the most deranged of all Marian phenomena occurred in Necedah, the tiny Wisconsin town where my mother grew up. Although she moved from Wisconsin to Chicago after WWII, she used to go to a shrine in Necedah (not far from Mauston and the Wisconsin Dells) light candles, and pray. She bought the full set of books detailing the Blessed Mother’s conversations with a woman named Mary Ann Van Hoof that began in 1950. As best I know she never read them. (My mother wasn’t a voracious reader like my father.) That’s a good thing. There was enough heartbreak in her life without her having to face the fact that Mary Ann was obviously insane and increasingly under the influence of a very shady John Bircher type named Henry Swan. From standard exhortations to pray the rosary and live a moral, Christ-centered life, the messages became ever more reactionary and eventually hateful. Some were innocuously crazy; Mary Ann dutifully reported the Blessed Mother’s warnings against miniature Soviet submarines sneaking up the St. Lawrence river. But many of her later messages described a worldwide conspiracy of Jews (whom she called “yids”) rooted in the United Nations and the Baha’i Temple in Chicago. Oh, and the Russians were planning all sorts of attacks, most of them sneaky things like poisoning food, water, and farm animals.

The local Roman Catholic bishop condemned the apparitions in 1955, and soon after issued interdicts against Mary Ann and her followers. Still, Mary Ann stayed the course, and continued writing down Mary’s messages (with plenty of help from Henry Swan) until her death in 1984.

The first thing I learned about Marian apparitions is that the Lady gets around: There have been lots and lots of them, most occurring in the midlate 20th Century. This is the best list of apparitions I’ve found. (There was even one here in Scottsdale in 1988.) For every apparition approved by the Church as acceptable private revelation, there are probably fifty either ignored, or (as in Necedah) actively condemned. The second thing I learned is that they’re almost always warnings of dire things to come if we don’t straighten up our acts. The third thing I learned is that the craziness was not limited to Necedah, though Henry Swan did his best to make it a cultural trope. The late and lamented (but still visible) suck.com did a wry article on the topic in 2001, highlighting the Blessed Mother’s ongoing battle against communism. The apocalyticism got utterly over-the-top at some point, with warnings against “three days of darkness” during which devils would be released from hell to scratch at our doors in an effort to steal our souls.

At that point, I figured I knew all that I cared to know, and the Scary Mary books went back on the shelves, where they remained, mostly untouched, until we packed our Colorado Springs house in 2015.

So what’s going on here? There’s a very good book on the subject by an objective outsider: Encountering Mary by Sandra L. Zimdars-Swartz . Most of her discussion centers on approved apparitions, but she does touch on the crazy stuff, including Necedah. She takes a sociological approach, is very careful not to be judgemental, and never implies that we might be dealing with psychopathology here, even in the crazy phenomena like Necedah.

I won’t be as courteous. I’m pretty sure we’re dealing with the mechanisms of charismatic religion here, which can be fine until a certain line is crossed. I have a theory about the crazy ones that as best I know is original to me: Visionaries like poor Mary Ann Van Hoof are indeed high-functioning schizophrenics, but more than that, are relics of an age described by Julian Jaynes back in the 1970s as the age of the “bicameral mind.” Jaynes’ book The Origin of Consciousnes in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind is a slog but still worth reading.

It’s complicated (what isn’t?) but Jaynes’ theory is that until around 3000 BC, human minds worked differently than they do today. The left brain was somewhat of a robot, with little or no sense of itself, and the right brain was where everything important happened. The right brain gave the left brain orders that took the form of voices heard in the left brain’s speech centers. Primitive humans first thought of the voices as those of their deceased relatives, and later as disembodied gods. In a sense, Jaynes is claiming that humans evolved as schizophrenics with a much thinner wall between the two hemispheres of the brain. At some point, the left brain became capable of introspection, allowing it to take the initiative on issues relating to survival, and the wall between the hemispheres became a lot less permeable. According to Jaynes, ego trumped schiophrenia in the survival olympics, and the bicameral mind was quickly bred out of the human creature.

I won’t summarize his arguments, which I don’t entirely accept. I’m looking at it as a potential gimmick in my fiction, which is the primary reason I read in the category I call “weirdness.” However, the similarity of Jaynes’ bicameral mind concept and what happens in many ecstatic visions (in Christianity and other religions) struck me. We still have schizophrenics among us, and we may have individuals where schizophrenia lurks just beneath the surface, waiting for a high-stress event to crack a hole in the hemispheric barrier and let the voices come through again. The key is that Marian apparitions are almost always crisis-oriented. Mary never just drops in to say “Hi guys, what’s going on?” In a Marian context, the crises are almost always moral and sometimes ritual, warning against the consequences of abandoning traditional beliefs and/or sacramental worship. The occasional gonzo apparitions (like Necedah and another at Bayside, NY) plunge headfirst into reactionary secular politics as well. A threat to the visionary’s deepest beliefs can trigger apocalyptic warnings through voices that the visionary interprets as Mary, Jesus, or some other holy person.

Whether all or even the greater part of Jaynes’ theory is correct, it’s pretty likely that there are mechanisms in the brain that we have evolved away from, and these “voices of the gods” may be one of them. The right brain is a powerful engine, and it doesn’t have much in the line of communication channels to the left hemisphere right now. Writing can be one of them. I’m what they call a “pantser” on the fiction side. In fact, I’m a “gateway writer,” meaning that I write whole complicated scenes without a single bit of planning aforethought. I don’t outline my novels. I vomit them onto disk, jumbled in spots but mostly whole. How does that even work?

And what else could we do if we could crack that valve a little wider?

My gut (which is in fact my right brain) whispers, “Nothing good. The left brain evolved to protect the right brain from itself. Evolution knew what it was doing. Not all of those voices were gods.”

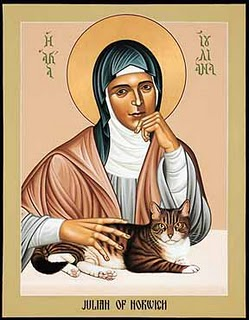

Today is Mother’s Day, and I celebrate it in eternal memory of Victoria Albina Pryes Duntemann 1924-2000. But today is also something else: May 8, the feast day of

Today is Mother’s Day, and I celebrate it in eternal memory of Victoria Albina Pryes Duntemann 1924-2000. But today is also something else: May 8, the feast day of  Already done: “And so our good Lord answered to all the questions and doubts which I could raise, saying most comfortingly: I may make all things well, and I can make all things well, and I shall make all things well, and I will make all things well; and you will see yourself that every kind of thing will be well.” Julian of Norwich, Showings, Chapter XXXI.

Already done: “And so our good Lord answered to all the questions and doubts which I could raise, saying most comfortingly: I may make all things well, and I can make all things well, and I shall make all things well, and I will make all things well; and you will see yourself that every kind of thing will be well.” Julian of Norwich, Showings, Chapter XXXI.