1969 gave us the Summer of Love, though we (and I especially) didn’t know it at the time. Back then I thought of it as The Summer We Landed on the Moon, and to a lesser extent The Summer I Filled the Garage with Broken Radios and TVs. It was the summer I turned 17, between junior and senior years at Lane Technical High School in Chicago. It was the summer my big home-made 10″ Newtonian telescope finally (after three years of hard work) saw first light. It was the summer I got my first job, washing dishes at the Walgreen’s Grill at Harlem and Foster Avenues. It all seemed dazzling the way that most things do to young people who haven’t drunk the corrosive kool-aid of cynicism, because so much of it was new to us.

1969 gave us the Summer of Love, though we (and I especially) didn’t know it at the time. Back then I thought of it as The Summer We Landed on the Moon, and to a lesser extent The Summer I Filled the Garage with Broken Radios and TVs. It was the summer I turned 17, between junior and senior years at Lane Technical High School in Chicago. It was the summer my big home-made 10″ Newtonian telescope finally (after three years of hard work) saw first light. It was the summer I got my first job, washing dishes at the Walgreen’s Grill at Harlem and Foster Avenues. It all seemed dazzling the way that most things do to young people who haven’t drunk the corrosive kool-aid of cynicism, because so much of it was new to us.

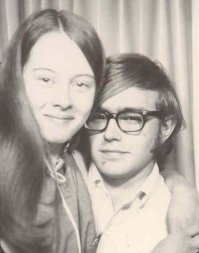

We rarely see history happening the way the future will see it. Time is actually what writes history, with all of us peeking over Time’s shoulder and shouting our opinions as to what really mattered and what was just entertainment or distraction. I didn’t see it then, and it took a few years for the realization to sink in, but the summer of 1969 was the most important summer of my entire life. Why? It was the summer I met Carol, who was first my girlfriend, and soon after my best friend and confidant, later on my fiancee, and eventually my spouse. I told the details of the story of our meeting in this space five years ago, so today, I’ll fill in some of the backstory, as a possible answer to the question we frequently hear: How did you make it work?

Well, similarity was a very good start. Opposites do attract–and then, like protons and antiprotons, generally annihilate one another. Carol and I were both middle-class urban Baby Boomers. We lived in small houses near the northwest corner of Chicago: Me just inside the city limits, she just outside, in the bordering suburb of Niles. We were “good kids” of careful and loving parents, who simply expected that excellence would be demonstrated at school and good manners would be demonstrated everywhere, at all times. Honest mistakes would be tolerated, but misbehavior was unthinkable. Neither of our families were especially flush, but we both had all that we needed, and if there was any restlessness in either of us, it hid well.

I was nerdy but not asocial; in fact, as I progressed through my (all-male) high school, I became a sort of alpha geek, and was president of the Lane Tech Amateur Astronomical Society for two years, a position that carried considerable prestige and a coterie of like-minded and enthusiastic followers. I finished our basement on Clarence Avenue in knotty pine paneling when I was 14, and spent a lot of time down there writing science fiction, building telescopes, and tinkering with electronics. At the time I considered loneliness to be part of the landscape of ordinary life. My best friend Art Krumrey and I took long walks and talked endlessly about having girlfriends without achieving any remarkable insights. I’ll admit that Art had a better grip on it than I did, and the first real date I ever went on was a blind outing with his first girlfriend’s best girlfriend, who in truth didn’t much care for what Art and Rosemary had handed her, and nothing came of it.

I was nerdy but not asocial; in fact, as I progressed through my (all-male) high school, I became a sort of alpha geek, and was president of the Lane Tech Amateur Astronomical Society for two years, a position that carried considerable prestige and a coterie of like-minded and enthusiastic followers. I finished our basement on Clarence Avenue in knotty pine paneling when I was 14, and spent a lot of time down there writing science fiction, building telescopes, and tinkering with electronics. At the time I considered loneliness to be part of the landscape of ordinary life. My best friend Art Krumrey and I took long walks and talked endlessly about having girlfriends without achieving any remarkable insights. I’ll admit that Art had a better grip on it than I did, and the first real date I ever went on was a blind outing with his first girlfriend’s best girlfriend, who in truth didn’t much care for what Art and Rosemary had handed her, and nothing came of it.

Carol was quieter than I, and a lot less eccentric. She pursued straight A’s with tremendous energy (managing to be double-promoted past third grade) and yet was described as “serene” by her classmates. She was grace under pressure, in spades: calm, precise, and capable of summoning focused enthusiasm without falling all over herself, as I sometimes did. Beyond academics (especially science) her two big interests were dance and drama, and she appeared in the major high school plays produced by her school all four years she was there. These were not casual, small-time things, but full-blown musical comedies, including The Boyfriend and My Fair Lady. I’ve seen professional theater that was done with less skill and cruder production values. She had plenty of poise but was quite shy, and while she spoke occasionally with boys in her neighborhood, she attended an all-girl Catholic high school, and didn’t mix a lot with the opposite sex. Her parents told her she could not date until she turned 16. The week after her 16th birthday, she went on her first date, with a boy from her neighborhood. Two weeks after her 16th birthday, well, there we were, and the world changed.

Carol was quieter than I, and a lot less eccentric. She pursued straight A’s with tremendous energy (managing to be double-promoted past third grade) and yet was described as “serene” by her classmates. She was grace under pressure, in spades: calm, precise, and capable of summoning focused enthusiasm without falling all over herself, as I sometimes did. Beyond academics (especially science) her two big interests were dance and drama, and she appeared in the major high school plays produced by her school all four years she was there. These were not casual, small-time things, but full-blown musical comedies, including The Boyfriend and My Fair Lady. I’ve seen professional theater that was done with less skill and cruder production values. She had plenty of poise but was quite shy, and while she spoke occasionally with boys in her neighborhood, she attended an all-girl Catholic high school, and didn’t mix a lot with the opposite sex. Her parents told her she could not date until she turned 16. The week after her 16th birthday, she went on her first date, with a boy from her neighborhood. Two weeks after her 16th birthday, well, there we were, and the world changed.

The seed crystal at the center of that change was a desire for genuine friendship with the opposite sex. I had actually had a little practice in that with the little girl three doors down, and hugely enjoyed the camaraderie, even though hormones had intruded by the time we were 14 and ruined what had been a remarkable preteen friendship. I was determined not to make that same mistake twice. Carol and I went to movies and plays and other entertainments, but we also took long walks, delighting in  conversation, each for separate reasons not well understood, even by ourselves. Here was a boy who enjoyed talking, and could talk about all kinds of things–and here was a girl who enjoyed talking, and didn’t think conversation about astronomy and the mysteries of the fourth dimension were invariably the symptoms of derangement. Once again, it worked: We became fast friends, and although we went to conventional school dances and five or six weeks in shared our first kiss, all that went on between us existed within a matrix of friendship nourished by conversation, in person and in a stream of letters that flew back and forth across the three miles that separated us, on a more than weekly basis. Six months after we met, in the thick of a particularly intense conversation that has otherwise been forgotten, Carol told me that she loved me, and we both knew that it was true–not mere words stemming from giddy infatuation or social obligation, but something far more real than both, because they had emerged from genuine and unselfish friendship.

conversation, each for separate reasons not well understood, even by ourselves. Here was a boy who enjoyed talking, and could talk about all kinds of things–and here was a girl who enjoyed talking, and didn’t think conversation about astronomy and the mysteries of the fourth dimension were invariably the symptoms of derangement. Once again, it worked: We became fast friends, and although we went to conventional school dances and five or six weeks in shared our first kiss, all that went on between us existed within a matrix of friendship nourished by conversation, in person and in a stream of letters that flew back and forth across the three miles that separated us, on a more than weekly basis. Six months after we met, in the thick of a particularly intense conversation that has otherwise been forgotten, Carol told me that she loved me, and we both knew that it was true–not mere words stemming from giddy infatuation or social obligation, but something far more real than both, because they had emerged from genuine and unselfish friendship.

Another key issue (though I hate to use the term) is that we allowed one another space. We dated other people here and there, and although we both lived at home during our college years and went to local universities, we had the good sense not to go to the same university. We thus avoided overdosing on one another, and dodged the temptation to control one another’s lives by continuous smothering presence. When Carol left home for grad school in Minnesota in 1974, we managed the two-year separation far better than we might have had we been joined at the hip the full five years previous.

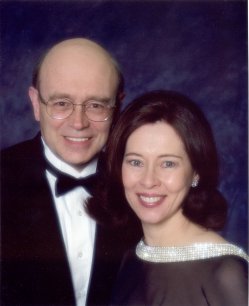

Everything else across forty years has proceeded from that simple foundation: Be friends, be patient, don’t smother, and talk about things. We’ve had arguments, including a couple of doozies, but once anger was spent, love flowed back in and started the conversation going again, so that healing could begin and the process of friendship continue.

Everything else across forty years has proceeded from that simple foundation: Be friends, be patient, don’t smother, and talk about things. We’ve had arguments, including a couple of doozies, but once anger was spent, love flowed back in and started the conversation going again, so that healing could begin and the process of friendship continue.

Finally, we learned along the way to recognize what was uniquely valuable in one another, and we leaned toward one another’s virtues as we grew into adulthood and then middle age. The process was slow, incremental, and sometimes extremely subtle–so much so that now and then we find ourselves thinking: Did I learn this from you or did you learn this from me? (The answer, of course, is a resounding Yes!) Not that the direction our virtues traveled really matters. The point is that we allowed ourselves to be changed in the cause of a friendship that we valued above all else in our lives, and that friendship has never disappointed us. Forty years has taught us that our friendship was well worth the effort; nay, that our friendship is in fact what being human is for.

Remarkably, we’ve kept in touch with Art and with Eileen, the girl that Art met that same night, as well as Jackie, Carol’s friend who introduced us on July 31, 1969. We’re all going to get together for a quiet dinner tonight, and raise a toast to the Summer of Love, forty years on but endless, as all really good summers always are.

We pulled into Crystal Lake last night after all the usual 1100 miles, with three adult bichons and an eight-and-a-half-week-old puppy in the hold. Redball is looking for two permanent names: A kennel name, and a call name. Kennel names are nominally unique (if often complex and sometimes ridiculous) and are how individual purebred dogs are listed in breed databases. QBit’s kennel name is Deja Vu’s Quantum Bit, and Aero’s is Jimi’s Admiral Nelson. Jackie’s kennel name is Jimi’s Hit the Jackpot. We went through a lot of ideas on the way out (Nebraska is good for such things) and floated possibilities like Jimi’s Morning Cloudscape. As for call names, well, that’s how you call the dog for dinner. Short is good. One of my favorites, after listening to him fuss halfway across Iowa, is Riesling, or Reese for short. Hey, he’s white and he whines. (Ceaselessly.)

We pulled into Crystal Lake last night after all the usual 1100 miles, with three adult bichons and an eight-and-a-half-week-old puppy in the hold. Redball is looking for two permanent names: A kennel name, and a call name. Kennel names are nominally unique (if often complex and sometimes ridiculous) and are how individual purebred dogs are listed in breed databases. QBit’s kennel name is Deja Vu’s Quantum Bit, and Aero’s is Jimi’s Admiral Nelson. Jackie’s kennel name is Jimi’s Hit the Jackpot. We went through a lot of ideas on the way out (Nebraska is good for such things) and floated possibilities like Jimi’s Morning Cloudscape. As for call names, well, that’s how you call the dog for dinner. Short is good. One of my favorites, after listening to him fuss halfway across Iowa, is Riesling, or Reese for short. Hey, he’s white and he whines. (Ceaselessly.)