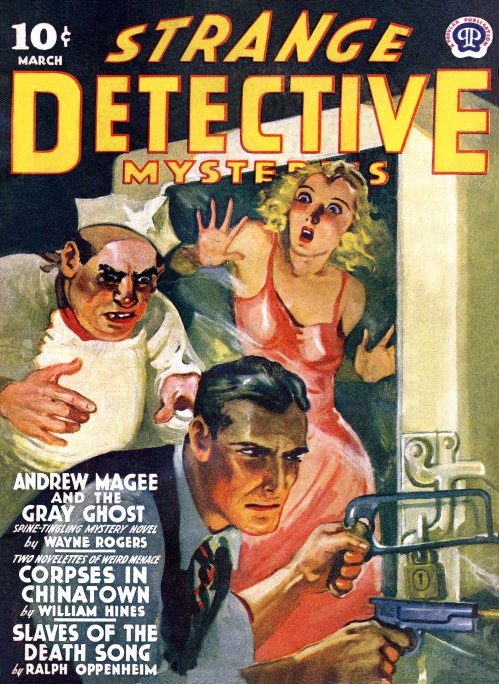

Bet you thought I forgot about this series, huh? Not so: I needed a little time to take a broader look at the field. (Click here for Part 1 and Part 2.) Someone told me that a lot of 1930s/40s/50s pulps were being scanned and posted on Usenet at alt.binaries.pictures.vintage.magazines, so I went up there and pulled down a representative sample. And I’m not talking SF anymore; what I grabbed were things like Air Wonder Stories, Mammoth Western, Strange Detective Mysteries, Adventure, and Spicy Stories.

It’s been wonderful fun. In fact, it’s a lot like watching campy old b/w TV shows, only better, because I can decide how everybody and everything looks. I don’t have to be appalled (or giggle) at the cheap crappy special effects. I just willingly enter a world in which nobody rolls their eyes at a homicidal supermarket butcher about to strangle a square-jawed hero armed with a pistol in one hand and a hacksaw in the other. (See above. No, I didn’t read that story. I still wonder what the hacksaw was about.)

I’m not the first to suggest that the pulps vanished largely because TV took over their niche. The pulps were Saturday-morning movie serials that you could enjoy any time you wanted, and once TV started showing Commando Cody, Bomba the Jungle Boy, Flash Gordon, and made-for-TV adventures like The Texas Rangers, Sky King and Highway Patrol, much of the money went out of pulp publishing. The financial pressure was eventually fatal, but over the short term, as the pulps dwindled, their quality went up. And it wasn’t just that we knew more about science and technology and hence could write better SF. The SF of the Thirties was awful because the readership didn’t care. The pulps had a monopoly on cheap entertainment and people bought it because it was all there was, and reading it was better than staring at the wall.

Print entertainment evolved out of the pulps and into other print markets, particularly glossy mags. The railroad pulps died, but glossy, ad-supported magazines like Trains and Railroad picked up the readership, which after WWII had more money to spend on locomotive picture books and model railroading. Tacky text-porn mags like Spicy Stories (which had racy drawings and a handful of “artful” b/w nude photos) gave way to Playboy and its cheaper imitators as social strictures against visual porn weakened in the 50s. In the late 50s, pulp SF improved hugely, and bootstrapped itself into the new world of mass-market paperbacks by selling reprint anthologies of the best work to come out of the pulp era. (We can be fooled into thinking 30s and 40s pulp SF was better than it was because what we read of it was hand-picked for quality decades after its publication. Read a couple of original SF pulps circa 1935 and you’ll see what I mean.) Crime pulps went both up and down, to comics on the low end (much of “crime” fiction from the Depression was actually horror) and to book-length mysteries on the high end. The romance pulps like My Romance split similarly into gossip mags and mass-market romance novels.

Fewer people may be reading these days, but those who gave it up probably never liked reading that much to begin with. Again, reading was better than staring at the wall, but TV, when it arrived, was easier, especially for people with marginal education. The audience that remained was pickier, and many had been formally exposed at the college level to classic literature, which became the standard by which all fiction was measured.

And that may be a mistake. (I’ll come back to this point in a future entry.)

Leaving the quality of the writing itself as a separate issue, after a good long look around I’d say that the lessons of the pulps are these:

- The pulps were about specific cultures. They were tightly linked to a time and a place and a generally understood cultural subtext. This was even true of early pulp SF, much of which might be characterized as “Depression-era Chicago on Mars.”

- Characters were intended as costumes to be worn by readers, not fully realized individuals to be admired on their own merits as independent men and women. A lot of people don’t understand this, and many still won’t admit it. Make characters too vividly fluky and original, and readers will have a hard time identifying with them.

- As a corollary to the above: Concepts, settings, and action were as important as characters, and much more vivid. Again, it’s the difference between imagining yourself driving a fast car and imagining someone else driving it.

- The pulps were fun. They understood and accepted their role as immersive entertainment. They were not equipped to be literature and didn’t try to be literature.

With all that in mind, the big questions become: Is there unmet demand today for good-quality immersive (non-literary) fiction? How much of this legacy can we retrieve in 2010 and do well?

More next time.