Among the people we miss most in Arizona are our then-neighbors Pat Thurman K7KR and his wife Sue “Starshine” Thurman. Back in 1998, Sue approached me about building her a sort of robotic ventriloquist’s dummy for a kid’s show she was working on (starring her character Starshine) to promote reading in grades 1-4. She wanted a character who looked like a robot, and suggested that Meccano might be just the thing. I’ve done a lot of Meccano work down the decades, and thought it was a great idea. I soon realized that a full-sized dummy would be mostly steel and weigh far too much to sit on anyone’s lap. As a counter proposal I suggested a disembodied robot head, which would be controlled by a puppeteer under a table. Sue loved it, and gave the character a name long before I finished designing and building him: The Head of R&D, aka “RAD.”

The show itself was no small production, and included a cameo by Jane Hull, then governor of Arizona. Sue worked fiendishly hard on it, and recruited many of her theater friends to play parts and generally help out. Carol played Madame LePinswick, a fortune-teller. I sat under the modified card table on which RAD was mounted, so that I could work the controls. RAD could turn his head from side to side, roll his eyes, move his bushy eyebrows independently, and work his jaw. All of this was done with a vertical control column running down from his neck, and with both hands on the controls (which resembled a movie-submarine periscope) I could do it all at once. Sure, it took some practice, but the range of expression RAD could display was surprising.

The inside of RAD’s head was a ratsnest of gears, sprocket chains, levers and push rods, and took a great deal of fooling-with to get right. During performances I sat on a peculiar folding beach chair underneath the card table, and watched the stage on a 9″ portable color TV so that I could see where everybody else was on stage and make RAD interact with them. (There was a CCTV camera mounted on a seat in the front row of the grade school auditorium where the show was presented.) Two of Sue’s friends were voice actors, and provided RAD’s slightly British voice and the voice of TC, the Heathkit Hero robot who was Starshine’s sidekick. I basically lip-synced RAD to his voice actor, who was off-stage with a mic. I added as much additional facial expression as I could manage, given that moving his mouth was primary.

Earlier today, Sue posted a video of the full-half-hour show on YouTube. RAD first appears at about 15:30. Carol appears at several points in the video, including a brief close-up with RAD at 25:00 and again at 26:05 and 30:00. My book The Delphi Programming Explorer makes a cameo at 30:34. RAD himself was later featured in an article in Constructor Quarterly (the Meccano hobbyist magazine) in the September 2000 issue.

After the live presentation to the students at the school where the video was filmed, several of the boys came up on stage so I could show them how RAD worked. One earnest 8-year-old asked me, “What number Erector set do you need to build that!” (By my calculation, he should be just about through engineering school by this time. I hope I gave him a nudge.) All in all, it was terrific fun, and as his 15th birthday approaches RAD still sits on my workbench, fully functional if maybe a little out of adjustment. I’m guessing he will always rank as the single most peculiar mechanical thingamajig I have ever put together. Many thanks to Sue for letting me get involved. I hadn’t seen the video in over ten years, and it was terrific to see it again.

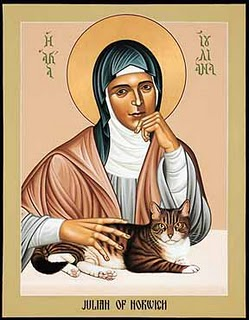

Today is Mother’s Day, and I celebrate it in eternal memory of Victoria Albina Pryes Duntemann 1924-2000. But today is also something else: May 8, the feast day of

Today is Mother’s Day, and I celebrate it in eternal memory of Victoria Albina Pryes Duntemann 1924-2000. But today is also something else: May 8, the feast day of  Already done: “And so our good Lord answered to all the questions and doubts which I could raise, saying most comfortingly: I may make all things well, and I can make all things well, and I shall make all things well, and I will make all things well; and you will see yourself that every kind of thing will be well.” Julian of Norwich, Showings, Chapter XXXI.

Already done: “And so our good Lord answered to all the questions and doubts which I could raise, saying most comfortingly: I may make all things well, and I can make all things well, and I shall make all things well, and I will make all things well; and you will see yourself that every kind of thing will be well.” Julian of Norwich, Showings, Chapter XXXI.

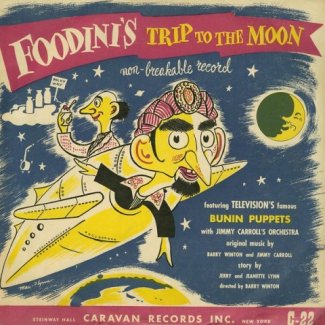

Like most record players in that era, it could do 33 1/3, 45, and 78 RPM. Most of my records were 45s. (The older ones, including Foodini, were 78s.) Playing a 45 at 33 1/3 was interesting for a moment but ultimately boring: Small children run at inherently higher clock rates than adults, and slow music is not a big draw. 78, now: I had a Disney extended-play 45 containing music from the 1955 “Lady and the Tramp” and I loved it a lot. One cut in particular was my favorite: “Lady,” the instrumental theme for the female cocker spaniel lead. It was bouncy (like me) and I quickly learned how to pick up the needle and drop it again at the beginning of the track, playing it again and again. And when that got boring, I nudged the speed lever up to 78.

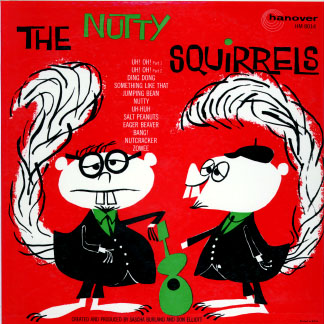

Like most record players in that era, it could do 33 1/3, 45, and 78 RPM. Most of my records were 45s. (The older ones, including Foodini, were 78s.) Playing a 45 at 33 1/3 was interesting for a moment but ultimately boring: Small children run at inherently higher clock rates than adults, and slow music is not a big draw. 78, now: I had a Disney extended-play 45 containing music from the 1955 “Lady and the Tramp” and I loved it a lot. One cut in particular was my favorite: “Lady,” the instrumental theme for the female cocker spaniel lead. It was bouncy (like me) and I quickly learned how to pick up the needle and drop it again at the beginning of the track, playing it again and again. And when that got boring, I nudged the speed lever up to 78. This was a fad in the late 1950s, starting with Sheb Woolley’s “Purple People Eater,” which had a couple of sped-up spoken vocals (“I wanna get a job in a rock and roll band…”) but no sped-up singing. That was a Seville invention, with his 1958 song “Witch Doctor,” setting the stage for The Chipmunks at Christmas time that year.

This was a fad in the late 1950s, starting with Sheb Woolley’s “Purple People Eater,” which had a couple of sped-up spoken vocals (“I wanna get a job in a rock and roll band…”) but no sped-up singing. That was a Seville invention, with his 1958 song “Witch Doctor,” setting the stage for The Chipmunks at Christmas time that year. We moved here from Arizona in 2003, and (as usual) it took us literally years to unpack everything. Some stuff was not meant to be unpacked, really–I left my vinyl collection and 8″ reel-to-reel mix tapes in boxes on the big shelf in the mechanical room, knowing they’d be there if I needed them but not actually expecting to need them. (I admit, I’ve gone looking in the boxes for a vinyl album a couple of times.) But there’s one box on the high shelf here in my office, containing stuff that was in odd places in my Scottsdale office, stuff that I wasn’t really sure where to put or what to do with. Every so often I sift through the box for an hour or so, trashing some stuff and filing some stuff and putting the rest of it back in the box. It’s only about 1/4 full now, so I guess I’m making some progress. It should be empty by the time I’m 80.

We moved here from Arizona in 2003, and (as usual) it took us literally years to unpack everything. Some stuff was not meant to be unpacked, really–I left my vinyl collection and 8″ reel-to-reel mix tapes in boxes on the big shelf in the mechanical room, knowing they’d be there if I needed them but not actually expecting to need them. (I admit, I’ve gone looking in the boxes for a vinyl album a couple of times.) But there’s one box on the high shelf here in my office, containing stuff that was in odd places in my Scottsdale office, stuff that I wasn’t really sure where to put or what to do with. Every so often I sift through the box for an hour or so, trashing some stuff and filing some stuff and putting the rest of it back in the box. It’s only about 1/4 full now, so I guess I’m making some progress. It should be empty by the time I’m 80.

Lora Heiny sent me a note this morning to tell me that her brother Loren had died during the night, after a four-year struggle with cancer. He was 49. Loren was an early expert on Tablet PC technology, and most of what I learned about it after I got my X41 in 2005 came from

Lora Heiny sent me a note this morning to tell me that her brother Loren had died during the night, after a four-year struggle with cancer. He was 49. Loren was an early expert on Tablet PC technology, and most of what I learned about it after I got my X41 in 2005 came from