Sixty years ago today, my parents were married, at St. Mary of Perpetual Help church on West 32nd Street in Chicago. It was a remarkable event, not so much because history will consider my parents remarkable (though I do) but because it was, well, unlikely. This remarkableness was not unique, but occurred countless times around America in that era, as social and ethnic barriers that had stood for centuries started to crumble, and men and women began to marry for love and not to satisfy family demands.

Sixty years ago today, my parents were married, at St. Mary of Perpetual Help church on West 32nd Street in Chicago. It was a remarkable event, not so much because history will consider my parents remarkable (though I do) but because it was, well, unlikely. This remarkableness was not unique, but occurred countless times around America in that era, as social and ethnic barriers that had stood for centuries started to crumble, and men and women began to marry for love and not to satisfy family demands.

Consider Frank William Duntemann, the only son of a bank officer at the First National Bank of Chicago. He had been born and raised solidly middle class in East Rogers Park, of a German father and an Irish mother. Hard-headed, ironic, optimistic, stubborn, bright, slightly snotty, and short–5’6″ of solid muscle, fearless and (especially as a young man) a little pugnacious. He drove his parents crazy sometimes, running off to join the Army in 1938 when he was only 16 (the Army sent him home) and getting suspended from Lane Tech for beating the crap out of the six-foot president of the Lane Tech Nazi Society, after the Nazi had made the mistake of stabbing my father in the stomach with a wood chisel during an argument.

And consider Victoria Albina Pryes, the youngest of ten children, born of penniless Polish immigrants in a ramshackle farmhouse in Stanley, Wisconsin. Artistic, fretful, possessed of a beautiful voice, pious to the point of mysticism, and ethereally beautiful, she trained as a nurse in Chicago after WWII and struggled with the question of what to do with her life. Her family thought she should become a nun, because her high-school sweetheart had died in the War, and that could only be a Sign. But she held back, and one day in 1946 a nursing school friend suggested a double date. Mary’s boyfriend knew this interesting guy from the North Side…

Frank was smitten. Victoria was terrified. He asked for her phone number, and in a panic she made something up. Undeterred, the man who had slept through the bombardment of Monte Cassino sent a postcard to her nursing school (we have that postcard) asking her to get in touch. Even though torn between what she felt to be her family and religious obligations and her own infatuation, she did. Not sure what to expect from a man so far removed from her ethnic heritage and socioeconomic class, what she found was passionate friendship. In 1948 he asked her to marry him. By then, there was no hesitation.

But it was not without challenges. Frank’s parents were furious. They had expected him to marry a nice German girl from the neighborhood. Instead, he had chosen a Polock farm girl living in what they considered the slums. Harry Duntemann was not a man to be trifled with, and he told his son to break it off. Harry had managed to browbeat Frank into a bookkeeper’s job that he hated, and was nagging him to return to Northwestern for a degree in business. But the War had changed Frank, as it had changed thousands of men who had been frightened boys the day after Pearl Harbor. Frank took his father aside and told him, “Look, I’ve made my decision and it’s not open to discussion. I’m going to marry Victoria, and then I’m going to Georgia to get my engineering degree on the GI Bill. If you want us to come back here, and if you want to see your grandchildren, you’d better start seeing things my way.”

Harry, perhaps recognizing his own stubbornness in his son, gulped and agreed. (And to ensure that his son would return from Georgia, helped buy him a house–on the North Side.) And so on that gorgeous June day in 1949, my parents made their Happy Beginning, bridging two widely disparate cultures, he confidently, she (as always) apprehensively.

By any measure it was a successful marriage. Frank and Victoria changed one another: He taught her confidence, and persuaded her that she was beautiful and worthy; she taught him moderation and compromise. She was not sure she wanted children, but he did; he was not sure that a gentle style of childrearing would work, but she did. They were in fact spectacular parents. They read to us, they bought us books, they insisted that we speak correctly and tell the stories of our days at the dinner table. My father threatened to call the Alderman if the Chicago Public Library refused to give me a library card for being underage. (I was six; you had to be seven.) I got the card. He gave me money for electronic parts and bought me a microscope; later, when I was deeply into junkbox telescopes, my mother always had a dollar for one more pipe fitting. We were not especially flush, and were taught frugality, but money was always there for things that mattered. Stubborn as he was, my father had the courage to avoid his own father’s mistakes: He told us that no matter what careers we chose, he would support us in that choice.

My father loved my mother fiercely, and the lesson was not lost on me. More than once, when I was sitting at the kitchen table doing my homework, my father came home from work a little early, went up behind my mother at the stove, kissed the top of her head, and told her he loved her. When I was fifteen, he made it explicit: “Love comes out of friendship. If you’re lucky and smart, you’ll marry your best friend.” I did as he said (and also as he did) and no better advice has ever been given to me.

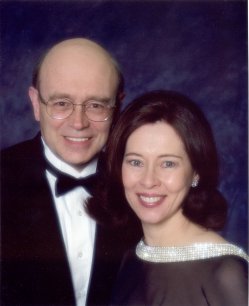

Happy beginnings are often easy. Alas, happy endings are not automatic. I’ve told most of the rest of the story here. In 1968 my father was diagnosed with oral cancer, from his two-pack-a-day habit he had picked up in Italy during the War. He fought back, and it took nine years, but the cancer killed him a piece at a time, in a gruesome progression that still gives me nightmares. It broke his spirit and finally took his mind; at our wedding in 1976 he was weak and confused. By 1977 he no longer knew who I was, which broke my heart, and in January 1978 it was finally over.

My mother was never the same. Living alone in their house for another 18 years allowed her to brood on questions of divine justice that had always haunted her. What had she done to offend God? How had she failed? My mother’s understanding of Catholicism was suffused with peasant superstition amplified to absurdity by her odd mystical personality. It was a cruel and often bizarre religion, full of prophecies and portents and dark powers, overlaid against the looming background of an angry God and an animate Hell. She was tormented by hideous dreams of accusing demons, dreams that may have led (as Gretchen and I have speculated) to the insomnia that plagued her last years. She was literally afraid to sleep, fearing what she might dream. Her doctors tried various drugs, but nothing helped, and even with Gretchen and Bill’s constant companionship and loving care, she lost her ability to speak, and slowly withered away to almost nothing. When I carried her out to Gretchen’s van the day before she died, she may have weighed fifty or sixty pounds, and looked like a victim of the Biafra famine.

It made me furious then, and I still get a little nuts to think about it. How can people who tried so hard, who loved one another so truly and unfailingly, who were generous and industrious and offered their children nothing but unconditional love, suffer such hideous ends? Where’s the justice here? The answers are complex, if in fact they are answers at all, and my readings on theodicy have been scant comfort.

Yes, they deserved a happy ending. And because they never had that happy ending, the day after my mother died in 2000, I sat down and wrote them one. (Warning: Major tearjerker material. The goal was closure, not publication.) They allowed me to be a writer, which is not as secure a career as an engineer (or almost anything else) so it was the least that I could do.

Still, the question stands: Where is the justice? If God does in fact exist, He owes me an answer to that painful question–but if God does in fact exist, (as I think He does) He’s already provided the answer–and the happy ending–to those, like my parents, who are farther along the Great Path than you or I.

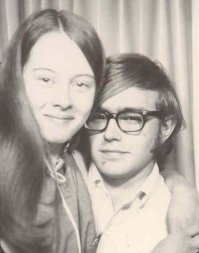

I’m doing a project for our church that involves scanning a lot of old photos, and while I’m at it, I’m scanning things that have been waiting in a ratty file pocket for scanning since, well, (in some cases) almost forever. Most are unremarkable, though a few of them are remarkable to Carol and me, like the first photo I ever took of her (at right) and the sheet of paper on which she wrote her phone number on the night we met. A few other things in the folder are odd indeed, though how odd depends on how strongly your taste buds respond to “odd.” So I’m going to present a couple of those odd things here and in coming days, just for fun.

I’m doing a project for our church that involves scanning a lot of old photos, and while I’m at it, I’m scanning things that have been waiting in a ratty file pocket for scanning since, well, (in some cases) almost forever. Most are unremarkable, though a few of them are remarkable to Carol and me, like the first photo I ever took of her (at right) and the sheet of paper on which she wrote her phone number on the night we met. A few other things in the folder are odd indeed, though how odd depends on how strongly your taste buds respond to “odd.” So I’m going to present a couple of those odd things here and in coming days, just for fun.

My mother had a drawer full of them in the 60s and 70s: These little things like shower caps, circles of plastic sheet of a sort you’d recognize from shower curtains, with an elastic gather around the edge. I actually called them “shower caps” in my head, and we used them to close half-used cans of mandarin orange segments and mushrooms. I didn’t think much about them until a year or two ago, when yogurt containers stopped coming with closable lids. I don’t toss back a whole 6 oz container of yogurt every morning, so this was a major irritation. In our climate, things dry out fast in the fridge, so putting something over an opened yogurt container is essential.

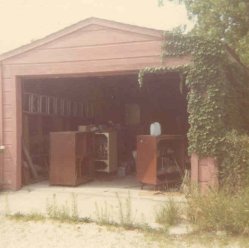

My mother had a drawer full of them in the 60s and 70s: These little things like shower caps, circles of plastic sheet of a sort you’d recognize from shower curtains, with an elastic gather around the edge. I actually called them “shower caps” in my head, and we used them to close half-used cans of mandarin orange segments and mushrooms. I didn’t think much about them until a year or two ago, when yogurt containers stopped coming with closable lids. I don’t toss back a whole 6 oz container of yogurt every morning, so this was a major irritation. In our climate, things dry out fast in the fridge, so putting something over an opened yogurt container is essential. 1969 gave us the Summer of Love, though we (and I especially) didn’t know it at the time. Back then I thought of it as The Summer We Landed on the Moon, and to a lesser extent The Summer I Filled the Garage with Broken Radios and TVs. It was the summer I turned 17, between junior and senior years at Lane Technical High School in Chicago. It was the summer my big home-made 10″ Newtonian telescope finally (after three years of hard work) saw first light. It was the summer I got my first job, washing dishes at the Walgreen’s Grill at Harlem and Foster Avenues. It all seemed dazzling the way that most things do to young people who haven’t drunk the corrosive kool-aid of cynicism, because so much of it was new to us.

1969 gave us the Summer of Love, though we (and I especially) didn’t know it at the time. Back then I thought of it as The Summer We Landed on the Moon, and to a lesser extent The Summer I Filled the Garage with Broken Radios and TVs. It was the summer I turned 17, between junior and senior years at Lane Technical High School in Chicago. It was the summer my big home-made 10″ Newtonian telescope finally (after three years of hard work) saw first light. It was the summer I got my first job, washing dishes at the Walgreen’s Grill at Harlem and Foster Avenues. It all seemed dazzling the way that most things do to young people who haven’t drunk the corrosive kool-aid of cynicism, because so much of it was new to us. I was nerdy but not asocial; in fact, as I progressed through my (all-male) high school, I became a sort of alpha geek, and was president of the Lane Tech Amateur Astronomical Society for two years, a position that carried considerable prestige and a coterie of like-minded and enthusiastic followers. I finished our basement on Clarence Avenue in knotty pine paneling when I was 14, and spent a lot of time down there writing science fiction, building telescopes, and tinkering with electronics. At the time I considered loneliness to be part of the landscape of ordinary life. My best friend Art Krumrey and I took long walks and talked endlessly about having girlfriends without achieving any remarkable insights. I’ll admit that Art had a better grip on it than I did, and the first real date I ever went on was a blind outing with his first girlfriend’s best girlfriend, who in truth didn’t much care for what Art and Rosemary had handed her, and nothing came of it.

I was nerdy but not asocial; in fact, as I progressed through my (all-male) high school, I became a sort of alpha geek, and was president of the Lane Tech Amateur Astronomical Society for two years, a position that carried considerable prestige and a coterie of like-minded and enthusiastic followers. I finished our basement on Clarence Avenue in knotty pine paneling when I was 14, and spent a lot of time down there writing science fiction, building telescopes, and tinkering with electronics. At the time I considered loneliness to be part of the landscape of ordinary life. My best friend Art Krumrey and I took long walks and talked endlessly about having girlfriends without achieving any remarkable insights. I’ll admit that Art had a better grip on it than I did, and the first real date I ever went on was a blind outing with his first girlfriend’s best girlfriend, who in truth didn’t much care for what Art and Rosemary had handed her, and nothing came of it. Carol was quieter than I, and a lot less eccentric. She pursued straight A’s with tremendous energy (managing to be double-promoted past third grade) and yet was described as “serene” by her classmates. She was grace under pressure, in spades: calm, precise, and capable of summoning focused enthusiasm without falling all over herself, as I sometimes did. Beyond academics (especially science) her two big interests were dance and drama, and she appeared in the major high school plays produced by her school all four years she was there. These were not casual, small-time things, but full-blown musical comedies, including The Boyfriend and My Fair Lady. I’ve seen professional theater that was done with less skill and cruder production values. She had plenty of poise but was quite shy, and while she spoke occasionally with boys in her neighborhood, she attended an all-girl Catholic high school, and didn’t mix a lot with the opposite sex. Her parents told her she could not date until she turned 16. The week after her 16th birthday, she went on her first date, with a boy from her neighborhood. Two weeks after her 16th birthday, well, there we were, and the world changed.

Carol was quieter than I, and a lot less eccentric. She pursued straight A’s with tremendous energy (managing to be double-promoted past third grade) and yet was described as “serene” by her classmates. She was grace under pressure, in spades: calm, precise, and capable of summoning focused enthusiasm without falling all over herself, as I sometimes did. Beyond academics (especially science) her two big interests were dance and drama, and she appeared in the major high school plays produced by her school all four years she was there. These were not casual, small-time things, but full-blown musical comedies, including The Boyfriend and My Fair Lady. I’ve seen professional theater that was done with less skill and cruder production values. She had plenty of poise but was quite shy, and while she spoke occasionally with boys in her neighborhood, she attended an all-girl Catholic high school, and didn’t mix a lot with the opposite sex. Her parents told her she could not date until she turned 16. The week after her 16th birthday, she went on her first date, with a boy from her neighborhood. Two weeks after her 16th birthday, well, there we were, and the world changed.

conversation, each for separate reasons not well understood, even by ourselves. Here was a boy who enjoyed talking, and could talk about all kinds of things–and here was a girl who enjoyed talking, and didn’t think conversation about astronomy and the mysteries of the fourth dimension were invariably the symptoms of derangement. Once again, it worked: We became fast friends, and although we went to conventional school dances and five or six weeks in shared our first kiss, all that went on between us existed within a matrix of friendship nourished by conversation, in person and in a stream of letters that flew back and forth across the three miles that separated us, on a more than weekly basis. Six months after we met, in the thick of a particularly intense conversation that has otherwise been forgotten, Carol told me that she loved me, and we both knew that it was true–not mere words stemming from giddy infatuation or social obligation, but something far more real than both, because they had emerged from genuine and unselfish friendship.

conversation, each for separate reasons not well understood, even by ourselves. Here was a boy who enjoyed talking, and could talk about all kinds of things–and here was a girl who enjoyed talking, and didn’t think conversation about astronomy and the mysteries of the fourth dimension were invariably the symptoms of derangement. Once again, it worked: We became fast friends, and although we went to conventional school dances and five or six weeks in shared our first kiss, all that went on between us existed within a matrix of friendship nourished by conversation, in person and in a stream of letters that flew back and forth across the three miles that separated us, on a more than weekly basis. Six months after we met, in the thick of a particularly intense conversation that has otherwise been forgotten, Carol told me that she loved me, and we both knew that it was true–not mere words stemming from giddy infatuation or social obligation, but something far more real than both, because they had emerged from genuine and unselfish friendship. Everything else across forty years has proceeded from that simple foundation: Be friends, be patient, don’t smother, and talk about things. We’ve had arguments, including a couple of doozies, but once anger was spent, love flowed back in and started the conversation going again, so that healing could begin and the process of friendship continue.

Everything else across forty years has proceeded from that simple foundation: Be friends, be patient, don’t smother, and talk about things. We’ve had arguments, including a couple of doozies, but once anger was spent, love flowed back in and started the conversation going again, so that healing could begin and the process of friendship continue.

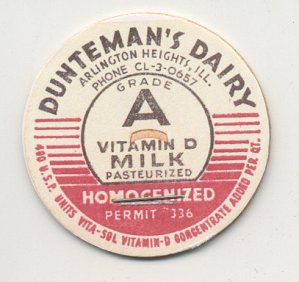

When I was a pre-teen, we used to get milk delivered to the house every few days. I don’t recall fersure which dairy it was (Hawthorn Mellody Farms?) but the milk was in massive gallon returnable glass bottles with wire carry-handles, and a paper cap was machine-pressed over the lip to seal it. The caps themselves were circular sheets of blank white paper, but stapled to the center of each cap was a printed cardboard disk about an inch and a half in diameter, containing the name of the dairy. The cardboard disks are now collectibles, related in a vague way to the juice-bottle “pogs” that were stylish for half an hour or so in the mid-1990s.

When I was a pre-teen, we used to get milk delivered to the house every few days. I don’t recall fersure which dairy it was (Hawthorn Mellody Farms?) but the milk was in massive gallon returnable glass bottles with wire carry-handles, and a paper cap was machine-pressed over the lip to seal it. The caps themselves were circular sheets of blank white paper, but stapled to the center of each cap was a printed cardboard disk about an inch and a half in diameter, containing the name of the dairy. The cardboard disks are now collectibles, related in a vague way to the juice-bottle “pogs” that were stylish for half an hour or so in the mid-1990s.