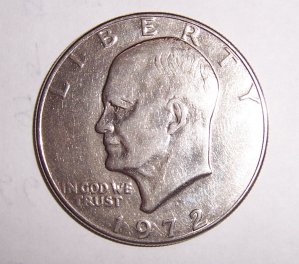

I finally got a Millard Fillmore dollar at the bank today. I’ve been meaning to ask for one for a long time, but I hate to bother the poor tellers for silly things like that when there’s a line. Today, for whatever reason, the Wells Fargo branch at Safeway was empty and staffers were standing around BSing, so I asked. And I got.

I finally got a Millard Fillmore dollar at the bank today. I’ve been meaning to ask for one for a long time, but I hate to bother the poor tellers for silly things like that when there’s a line. Today, for whatever reason, the Wells Fargo branch at Safeway was empty and staffers were standing around BSing, so I asked. And I got.

It’s a ridiculous coin in a lot of ways, none of them involving poor President Fillmore. Nobody uses dollar coins, and the government only issues them as a means of making something out of a nickel’s worth of metal and selling it to collectors for a dollar. The coins don’t suggest “money,” (and certainly don’t suggest “dollar”) and after only a little while in circulation they darken up and look like big ugly old pennies.

But I like Millard Fillmore, and have wanted to work him into a story for thirty years. I got closest in the fall of 1984, when someone in my SF group told me that Philip Jose Farmer was allowing people to write stories set in his Riverworld universe, as long as the yarns didn’t conflict with anything in the novels themselves. I have a collection of such stories, which were far better than what we now call fanfic, and are worth reading if you enjoyed Farmer’s epic even a little.

So I read up on Fillmore a little, and began a story. That was 26 years ago. I dug around in my two moving boxes full of old manuscripts downstairs just now, and found it without a great deal of trouble. Some quick OCR, and I can give you a sample:

It had been a quiet night, and the late night rains were past. Nicky was close by, too close: Through the merest wisp of thatch Fillmore heard female giggling. Soon, too soon, he suspected he would hear Nicky say something like, “I’ll do that again if you’ll go next door and be good to President Fillmore…” When the line worked, he felt wretched. When it didn’t work, he felt worse.

Fillmore had died an unhappy old prig at age 74, and even after thirty years on the great River, where everyone had been resurrected a healthy, glowing, eternal twenty-five, he had never gotten the knack for seducing young women who seemed more suitable to be his granddaughters than his paramours. Telling them he was Millard Fillmore virtually always produced a shrug–telling them he had been President of the United States usually brought forth a belly laugh.

For five years he had lived with a woman who had heard of him: Phyllis Swoboda, a twentieth-century American from Chicago. She had been a psychologist and was fascinated by what she called a “self-persecution complex manifested in a claim to be an unimportant historical figure.” She was clearly the one who was insane, but she had a magnificent memory, and she was from the future of America.

America! Phyllis told him tales of Apollo’s conquest of the Moon, the Panama Canal, Hoover Dam, personal computers, television, Chevrolets, and Space Shuttle Columbia. The most powerful, noble nation in the history of planet Earth, and he had led it for a little while. Wasn’t that worth something?

When Phyllis Swoboda couldn’t cure him of being Millard Fillmore, she moved on. Soon afterward, a tall, muscular blond man in a Panama hat approached him on the beach, set down his grail, and shouted, “You’re Millard Fillmore!” He had almost fainted.

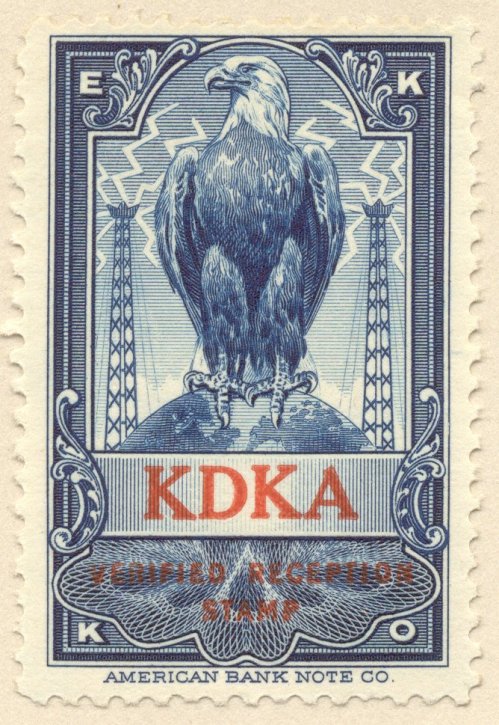

The man was Nicky Daniel Scroggins, who had died of polio in 1955 at twelve years of age. Nicky had collected stamps, and his favorite series of stamps had been the “Prexies,” issued in 1938, including every deceased President up to that year. On the 13-cent issue was the face of Millard Fillmore. “I had a whole sheet of you!” Nicky had shouted, and it was the beginning of the longest friendship Fillmore had enjoyed in either of his two long lives.

I doubt I would have sold it anywhere, but the story had some promise: Fillmore and Nicky trudge on along the River, where they find an “America” every three or four hundred miles. Each of these ersatz Americas boasts a charismatic leader who claims to be someone like John F. Kennedy, FDR, or Andrew Jackson. In no case is this true, but in every case the phony Presidents tell Fillmore to hit the road. After having adventures and being insulted by Sam Clemens (“Millard Fillmore! The man who proved that no one can grow up to be President!”) they happen upon yet another America, a small enclave led cooperatively by three men who claim to be Franklin Pierce, Chester A. Arthur, and Warren G. Harding. Conceding that there was little point in falsely claiming to be Millard Fillmore, the three obscure former presidents welcome Fillmore and make him the fourth partner in ruling the cooperative. (Somehow I flash on a Victorian steampunk epic entitled The League of Unexceptional Presidents.)

I got a few thousand words down, but the story had started to wander when I set it aside. Shortly afterward, I took the job with PC Tech Journal, and my SF career went into near-immediate eclipse. Still, I’m glad I tried: It was the only time I had ever attempted to write a story set in someone else’s world, and that whole challenge gave the project a very weird feel. I had to be careful not to be too imaginative, for fear of violating the fabric of the Riverworld saga, and I wasn’t used to putting artificial limits on my inventiveness. That, of course, is a core skill of a really good writer, and anyone who claims to be a master of his/her craft should try it.

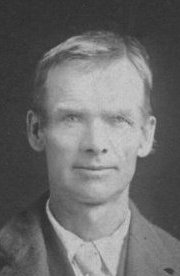

Not much. But it’s an interesting sort of detective work, this family resemblances stuff. I do know that my great-great grandfather Heinrich Duntemann 1843-1892 had four brothers, all of whom long survived him, who died of an infection from a farm injury at 48. I have photos of two of his brothers, William Duntemann 1849-1921 (left) and Hermann Duntemann 1859-1933. (right). William’s photo was taken when he was in his sixties, as best I know. Hermann’s was taken when he was 26. If I had to guess, I’d say that the leftmost man in the group photo was William, and the rightmost was Hermann. The remaining man may have been Louis Duntemann 1851-1928. I can’t tell, as I’ve never seen a photo and know very little about him.

Not much. But it’s an interesting sort of detective work, this family resemblances stuff. I do know that my great-great grandfather Heinrich Duntemann 1843-1892 had four brothers, all of whom long survived him, who died of an infection from a farm injury at 48. I have photos of two of his brothers, William Duntemann 1849-1921 (left) and Hermann Duntemann 1859-1933. (right). William’s photo was taken when he was in his sixties, as best I know. Hermann’s was taken when he was 26. If I had to guess, I’d say that the leftmost man in the group photo was William, and the rightmost was Hermann. The remaining man may have been Louis Duntemann 1851-1928. I can’t tell, as I’ve never seen a photo and know very little about him.

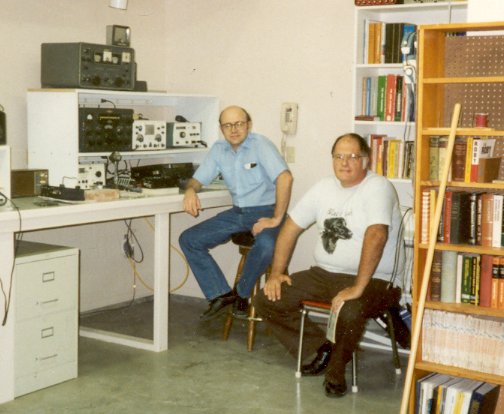

I first ran into George at the Clarion SF Writers’ Conference in East Lansing, Michigan, in 1973. That’s him on the right margin of the photo at left, holding a camera. (The other two workshoppers shown are Alan Brennert, far left, and Seth MacEvoy, center. There’s a chap between Seth and George whom I don’t recognize.) As WN9MQY, I had thrown my novice ham station into the trunk of my Chevelle and taken it with me, imagining running a wire from a third-floor dorm room out to one of the campus’s abundant trees. No luck; we were in the basement of Mason-Abbot Hall, and the only thing outside my room window were yew bushes…and a copper downspout. Hmmm. I poked a run of coax out the window and ran around outside to see whether I could somehow match into the copper pipe…and found another piece of coax in the dirt, coming from the next window over from mine. That’s when I met George Macdonald Ewing WA8WTE. Neither of us ever got a good match into the downspout, but that was all right. He became a close friend and my staunchest ally at the conference (which was a continuous low-key war between the Techs and the Orteests) and we were never out of touch for long after that.

I first ran into George at the Clarion SF Writers’ Conference in East Lansing, Michigan, in 1973. That’s him on the right margin of the photo at left, holding a camera. (The other two workshoppers shown are Alan Brennert, far left, and Seth MacEvoy, center. There’s a chap between Seth and George whom I don’t recognize.) As WN9MQY, I had thrown my novice ham station into the trunk of my Chevelle and taken it with me, imagining running a wire from a third-floor dorm room out to one of the campus’s abundant trees. No luck; we were in the basement of Mason-Abbot Hall, and the only thing outside my room window were yew bushes…and a copper downspout. Hmmm. I poked a run of coax out the window and ran around outside to see whether I could somehow match into the copper pipe…and found another piece of coax in the dirt, coming from the next window over from mine. That’s when I met George Macdonald Ewing WA8WTE. Neither of us ever got a good match into the downspout, but that was all right. He became a close friend and my staunchest ally at the conference (which was a continuous low-key war between the Techs and the Orteests) and we were never out of touch for long after that. Like me, he was a hands-on techie and hard SF enthusiast, and we brainstormed SF ideas and critiqued one another’s fiction frequently both at Clarion and afterward, in letters (later electronically) and in person. He was encouraging but also honest: In 1977, while visiting us in Chicago, he persuaded me to abandon a novel I was working on, and kidded me goodnaturedly about some of its more juvenile aspects for years thereafter. He sent a newsletter/fanzine to our Clarion class for the rest of the 70s, run off on the ditto machine of the rural Michigan high school where he taught. Alas, the termites made a colony out of my box of fanzines and APAs in the late 90s, and they’ve all perished, but George’s Post-Clarion Carrion was nicely done and often hilarious, especially his off-the-wall SF movie reviews. He attended our wedding in 1976 (above) and we saw him at SF cons regularly over the years. He and I were among the founders of the SF/tech fan group General Technics, a group that persists to this day.

Like me, he was a hands-on techie and hard SF enthusiast, and we brainstormed SF ideas and critiqued one another’s fiction frequently both at Clarion and afterward, in letters (later electronically) and in person. He was encouraging but also honest: In 1977, while visiting us in Chicago, he persuaded me to abandon a novel I was working on, and kidded me goodnaturedly about some of its more juvenile aspects for years thereafter. He sent a newsletter/fanzine to our Clarion class for the rest of the 70s, run off on the ditto machine of the rural Michigan high school where he taught. Alas, the termites made a colony out of my box of fanzines and APAs in the late 90s, and they’ve all perished, but George’s Post-Clarion Carrion was nicely done and often hilarious, especially his off-the-wall SF movie reviews. He attended our wedding in 1976 (above) and we saw him at SF cons regularly over the years. He and I were among the founders of the SF/tech fan group General Technics, a group that persists to this day. George was a published writer in both the SF and nonfiction worlds. His first story, “Black Fly,” appeared in Analog in September 1974, followed by semiregular publication there, in Asimov’s, and other places. He sold numerous articles into the electronics/ham radio market, many focused on scrounge technology. In 1983 Wayne Green Publications published George’s book Living on a Shoestring, which was a Ewing brain dump on how to do more with less and repurpose what you and I might call junk into the raw materials of a comfortable (if eccentric) life. It’s as close to a memoir as we’ll ever have, as those who knew him will attest. He was always doing this stuff, and developed a sense for outside-the-box make-do technology that served him well both personally and in his fiction. He was Pro Guest of Honor at Nanocon 8 in Houghton, Michigan, in 1996, and the Houghton SF group published a short reprint volume of his fiction for the con. He played tuba in his high-school band, and considered tuba one of his iconic traits. I never actually saw a tuba in his hands, but he drew cartoons of himself playing one on regular occasions–often standing atop unlikely things like abandoned military radar antennas.

George was a published writer in both the SF and nonfiction worlds. His first story, “Black Fly,” appeared in Analog in September 1974, followed by semiregular publication there, in Asimov’s, and other places. He sold numerous articles into the electronics/ham radio market, many focused on scrounge technology. In 1983 Wayne Green Publications published George’s book Living on a Shoestring, which was a Ewing brain dump on how to do more with less and repurpose what you and I might call junk into the raw materials of a comfortable (if eccentric) life. It’s as close to a memoir as we’ll ever have, as those who knew him will attest. He was always doing this stuff, and developed a sense for outside-the-box make-do technology that served him well both personally and in his fiction. He was Pro Guest of Honor at Nanocon 8 in Houghton, Michigan, in 1996, and the Houghton SF group published a short reprint volume of his fiction for the con. He played tuba in his high-school band, and considered tuba one of his iconic traits. I never actually saw a tuba in his hands, but he drew cartoons of himself playing one on regular occasions–often standing atop unlikely things like abandoned military radar antennas. I don’t have many good pictures of George. What’s here is all there is. The photo at the top of this entry was taken in 1995, in my then-new Scottsdale workshop. Sure, he’s peeking out from behind other people in various convention group shots, but mostly we see half of his head and one arm. The photo at left is the most recent I have, from 2004, with his mother June and his dog Tazzy. He didn’t think people were that interested in seeing his image; he sent me this photo only because he thought Tazzy looked like my old dog Smoker. (She does.) That was a key George Ewing characteristic: He was not full of himself. He was courteous, jovial, a good listener, generous with his time and ideas, and extraordinarily social. He was always willing to assume the best about other people, and never engaged in the sorts of poisonous arguments and personal attacks that have made so many others (including far too many in my acquaintence) look like brain-damaged twelve-year-olds. He scolded me only a couple of times, but always in private, and in every case for abundant good reason.

I don’t have many good pictures of George. What’s here is all there is. The photo at the top of this entry was taken in 1995, in my then-new Scottsdale workshop. Sure, he’s peeking out from behind other people in various convention group shots, but mostly we see half of his head and one arm. The photo at left is the most recent I have, from 2004, with his mother June and his dog Tazzy. He didn’t think people were that interested in seeing his image; he sent me this photo only because he thought Tazzy looked like my old dog Smoker. (She does.) That was a key George Ewing characteristic: He was not full of himself. He was courteous, jovial, a good listener, generous with his time and ideas, and extraordinarily social. He was always willing to assume the best about other people, and never engaged in the sorts of poisonous arguments and personal attacks that have made so many others (including far too many in my acquaintence) look like brain-damaged twelve-year-olds. He scolded me only a couple of times, but always in private, and in every case for abundant good reason. Life is full of little weirdnesses, and here’s yet another: Shortly before we left for Hawaii last month, my lucky dollar turned up missing. That’s the very one at left, though it’s shinier and more worn now than it was when

Life is full of little weirdnesses, and here’s yet another: Shortly before we left for Hawaii last month, my lucky dollar turned up missing. That’s the very one at left, though it’s shinier and more worn now than it was when

There was some stress on Tuesday night when Carol’s mom fell at her home outside Chicago and was taken to the hospital. She didn’t break anything, fortunately, but had to spend Christmas in a hospital bed. To cheer her up I put an SX270 system on the coffee table by the Christmas tree and set up a Skype video call with my nephew Brian. The hospital has Wi-Fi in the rooms, and Brian set his new laptop up on Delores’s bed tray. So by virtue of my Phillips ToUCam and Brian’s built-in Webcam, she could see us, the dogs, and the Christmas tree. Delores was delighted, and it’s a technique to keep in mind if you find yourself in such a situation. Skype is very good with detecting and autoconfiguring Webcams, and there was no fussing involved. I plugged in the ToUCam, made the call, and video happened. It’s not exactly a flying car, but it’s definitely one of those odd Sixties dreams fulfilled, mostly when nobody was looking.

There was some stress on Tuesday night when Carol’s mom fell at her home outside Chicago and was taken to the hospital. She didn’t break anything, fortunately, but had to spend Christmas in a hospital bed. To cheer her up I put an SX270 system on the coffee table by the Christmas tree and set up a Skype video call with my nephew Brian. The hospital has Wi-Fi in the rooms, and Brian set his new laptop up on Delores’s bed tray. So by virtue of my Phillips ToUCam and Brian’s built-in Webcam, she could see us, the dogs, and the Christmas tree. Delores was delighted, and it’s a technique to keep in mind if you find yourself in such a situation. Skype is very good with detecting and autoconfiguring Webcams, and there was no fussing involved. I plugged in the ToUCam, made the call, and video happened. It’s not exactly a flying car, but it’s definitely one of those odd Sixties dreams fulfilled, mostly when nobody was looking.

tracks, yapping furiously at it until he got bored. Pete Albrecht unexpectedly sent me a rare artifact indeed: An original Lionel 275W ZW dual-control transformer (right) that was probably made in the midlate 1950s. It works great, and can control two independent track sections and two independent sets of accessories.

tracks, yapping furiously at it until he got bored. Pete Albrecht unexpectedly sent me a rare artifact indeed: An original Lionel 275W ZW dual-control transformer (right) that was probably made in the midlate 1950s. It works great, and can control two independent track sections and two independent sets of accessories.

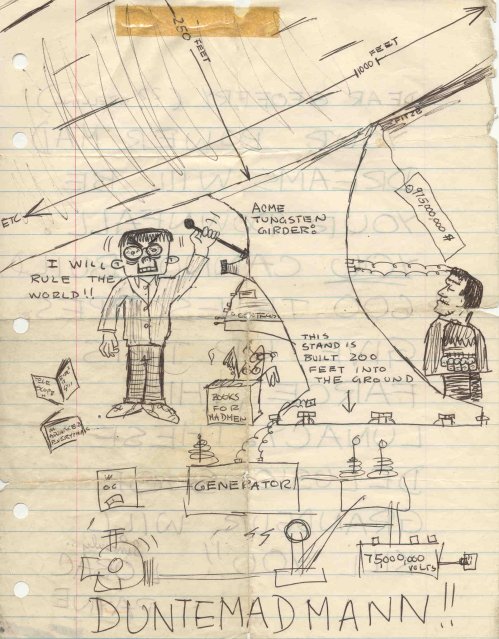

We sat in left-to-right rows of one-armed-charlies, and being in the middle, my writing surface was ground-zero for anarchic drawing competitions between the two of them. Fitze would dash something out, and then Ebenstein would add a monster in a corner, or a quick sketch of the Gray Mouser drawing his sword, or caricatures of the other kids in the class. Fitze would then add more monsters, guns, bombs, or bizarre superheroes, with captions like “Suction Man Sings Songs from the Twenties.” There was no particular sense to it, but the drawings were incisive and sometimes hilarious. For no reason I could name, I still have a folder full of papers from high school, running from Spanish quizzes to trigonometry exercises, plus a couple dozen sheets saved from aviation shop, full to the edges of vintage Fitze & Ebenstein.

We sat in left-to-right rows of one-armed-charlies, and being in the middle, my writing surface was ground-zero for anarchic drawing competitions between the two of them. Fitze would dash something out, and then Ebenstein would add a monster in a corner, or a quick sketch of the Gray Mouser drawing his sword, or caricatures of the other kids in the class. Fitze would then add more monsters, guns, bombs, or bizarre superheroes, with captions like “Suction Man Sings Songs from the Twenties.” There was no particular sense to it, but the drawings were incisive and sometimes hilarious. For no reason I could name, I still have a folder full of papers from high school, running from Spanish quizzes to trigonometry exercises, plus a couple dozen sheets saved from aviation shop, full to the edges of vintage Fitze & Ebenstein.