Michael Covington’s recent entry on the books that made him what he is intrigued me, and I spent an hour or so today gathering a similar list. I’m not sure that the 25 books listed below made me what I am, but each one of them changed me somehow, and sent me off in a direction that was slightly (and sometimes greatly) different from the path I had been on before. I’ve listed them chronologically in the order that I first read them, and the number in parentheses is my age at that time.

Note well that these are not all fabulous books, nor are all of the many fabulous books that I’ve read in my life listed here. These are the books that changed me in some identifiable way. It’s an interesting exercise, and I powerfully recommend it.

- Space Cat by Ruthven Todd (6). I don’t recall all of the books that my parents read to me, nor the first few I struggled through on my own, but it was the Space Cat series that made me an insatiable reader. Not all of what I read after that was SF, but it was SF that made me absolutely desperate to read.

- The Golden Book of Astronomy by Rose Wyler, Gerald Ames, and John Polgreen (6). My grandmother and Aunt Kathleen bought this for me for my sixth birthday. It’s a big book, filled with beautiful watercolors of stars, planets, telescopes and spacecraft, framed with text I could read myself. Once I finished it (and I read it countless times) I never looked at the night sky the same way ever again.

- Tom Swift and His Electronic Retroscope by Victor Appleton II (8). Tom Swift, Jr was my first exposure to YA SF, and this was the first Tom Swift book that I ever had. (It was no better and no worse than most of the others.) Although I had read YA SF and fantasy books earlier, Tom Swift touched a nerve and made technological SF an obsession.

- The American Heritage History of Flight by Arthur Gordon (10). This was the first history book of any kind that just took me by the throat and held on. I learned much about invention, and the debt that all inventors owe to those who came before them. I learned that failure is no disgrace, if the effort was diligent. This book helped me dream vividly, and Samuel Pierpont Langley became one of my earliest identifiable heroes.

- Using Electronics by Harry Zarchy (11). I’d read a couple of Alfred Morgan’s electronics books for preteens before, but Zarchy was a better engineer, and the circuits he described in his books just worked with less aggravation, when all you had were greasy second-hand parts tacked together with Fahnestock clips on a piece of scrap lumber. The book gave me the confidence to continue my study of electronics, which continues down to this day.

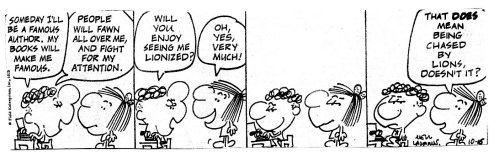

- Retief’s War by Keith Laumer (13). Although I’d read Laumer’s wry The Great Time Machine Hoax a few months before, it took Retief to drive home the conviction that SF could be funny. Humor is pervasive. There are humorous moments in most of my SF, even in serious stories like The Cunning Blood.

- Types of Literature ed. Edward J. Gordon (14). My high school was superb, and chose its textbooks well. This book, in its tank-rugged plain black binding, broadened my enjoyment of reading beyond SF and science to poetry, drama, essay, and “mainstream” fiction. I don’t know where else I would have encountered Southey’s “The Cataract of Lodore” or John Galsworthy’s “The Pack”.

- Spectrum 5, ed. Kingsley Amis (14). This was the book that (finally) nudged me beyond YA SF and Laumer’s simple and often silly adventures to genuine adult SF. I was stunned by the impact that Miller’s “Crucifixus Etiam” had on me, and when I wrote my first SF short story later that same year, it was the stories in Amis’s Spectrum series that I was imitating.

- The Lord of the Rings (14). As a young teen I was no fan of magicians and elves and suchlike, and if it had not been for the insistence of the first girl I ever cared deeply for I would never have touched it. Instead, I stood poleaxed before an entirely new creation, and I trace my love of SF world-building directly to Middle Earth.

- World of Ptavvs by Larry Niven (15). When Niven’s character Larry Greenburg sets Pluto on fire, I gasped, put the book down, and thought (about the book, not Pluto): I wanna do that! Laumer taught me how to write space adventures, but Niven taught me to think big.

- Of Time and Space and Other Things by Isaac Asimov (16). I always loved reading about science, but this was the first of many science books to impress me with the quality of the writing. Asimov’s written voice spoke to me as though he were right there across the kitchen table, talking to me as a friend would. When a few years later I first tried to write about technology, this was approach I would use.

- The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained by Henry P. Manning (16). For all the BS about the fourth dimension that I’d read in bad SF, this was the first book that allowed me to take higher dimensions seriously. The following year, my science fair project on four-dimensional geometry took me to the city competition and earned me a silver medal. It also shook loose (finally) the close connection between math and numbers and allowed me to look at difficult concepts from a height, conceptually. (The numbers fell into place later on. Sometimes.)

- Clarion, edited by Robin Scott Wilson (20). This is not an especially good book. In fact, when I read it I was appalled that some of the stories had even been published, and it all seemed to be due to this writers’ workshop that they had attended. So, having noticed from the introduction that the editor was local to me in suburban Chicago, I looked him up in the phone book and called him, and asked him how I could get into that workshop too. He told me. I applied. I was accepted. Six weeks after I got home, I sold my first story.

- TTL Cookbook by Don Lancaster (23). This was the book that first got me tinkering with digital logic. More than that, it went beyond Asimov toward my lifelong ideal of writing about technology as though I were talking across the table to a friend. This became my trademark, and ultimately sold a third of a million technical books with my name on them, plus four years of columns in Dr. Dobb’s Journal.

- Pascal Primer by David Fox and Mitchell Waite (30). I learned FORTRAN, FORTH, APL, COBOL, and BASIC before I ever encountered Pascal (and you wonder why I write my reserved words in uppercase!) but it wasn’t until I saw Pascal that I could say that I really loved programming. This odd looseleaf book with its offbeat cartoon illustrations proved to me that writing about programming could be enhanced by humor and good diagrams. I could not have begun Complete Turbo Pascal without reading this one first.

- Conjuror’s Journal by Frances L. Shine (35). Purchased for a dollar in the closeout bin somewhere, this understated novel of a mulatto parlor magician who wanders around Colonial America was the first book I can truly recall moving me to tears, and the one to which I trace my love of rural American settings and country people.

- The Lessons of History by Will and Ariel Durant (42). You can read this in an evening, and if you do, you will know why reading history is important. I got it in a stack at a Scottsdale garage sale, and have read at least a hundred histories since then, few of which I would have otherwise attempted.

- Good Goats by Dennis Linn, Sheila Linn, and Matthew Linn (43). The absurd cruelty of the idea of Hell (which eventually destroyed my mother) set me against religion for many years. This little book, more than any other, allowed me to start the long trip back.

- World Building by Stephen L. Gillett (45). The math behind astrophysics turned out not to be as scary as I had feared. And so I began creating not just imaginal worlds, but imaginal worlds that worked. 18 months later, I finished my first adult novel, The Cunning Blood.

- Julian of Norwich by Grace Jantzen (47). Wow! So my lifelong nutso optimism was not insane after all, and suddenly I had a patron saint. “All will be well, and all will be well, and all manner of thing will be well.” You go, girl!

- The Inescapable Love of God by Thomas Talbot (49). This book finally made it clear to me that I could be a universalist or else an atheist. There were no other choices. A God who doesn’t want to save all his creatures is not all-good; a God who can’t bring it about (without compromising our freedom) is not all-powerful, and God must be both in order to be God at all.

- Opening Up by James W. Pennebaker (51). To combat the deepening depression that began consuming me after my publishing company imploded in 2002, I undertook a program of “writing therapy” as outlined by Pennebaker. Maybe it didn’t save my life. It certainly saved my optimism, and got me back on the path after a nasty year of confronting the Noonday Devil.

- The Criminal History of Mankind by Colin Wilson (55). Right Men are the cause of most of the misery that humanity seemingly cannot avoid. I would never think about authority figures the same way after reading this. Trust no one who has power over you. No one.

- On Being Certain by Robert A. Burton, MD (56). This book put words to a suspicion I had had for some time: Certainty makes you a slave to that about which you are certain. A tribe, an ideology, anything. To be free you have to accept that all human minds (especially your own) have limitations, and that nothing–nothing!–can be known with certainty.

- Good Calories, Bad Calories by Gary Taubes (56). I’d been losing weight and getting healthier for ten years before I read this book, mostly by avoiding sugar. Now, finally, I understood why. I also now understand how Right Men like Ancel Keys can take almost any scientific field and turn it to crap. Good science requires that we be skeptical of all science, particularly science that obtains the endorsement of government, which (like pitch) defiles everything it touches.

I’m now 58, and it’s been a couple of years since any single book has changed the direction of my thought and my life. I’m about due for another. I’m watching for it.

We moved here from Arizona in 2003, and (as usual) it took us literally years to unpack everything. Some stuff was not meant to be unpacked, really–I left my vinyl collection and 8″ reel-to-reel mix tapes in boxes on the big shelf in the mechanical room, knowing they’d be there if I needed them but not actually expecting to need them. (I admit, I’ve gone looking in the boxes for a vinyl album a couple of times.) But there’s one box on the high shelf here in my office, containing stuff that was in odd places in my Scottsdale office, stuff that I wasn’t really sure where to put or what to do with. Every so often I sift through the box for an hour or so, trashing some stuff and filing some stuff and putting the rest of it back in the box. It’s only about 1/4 full now, so I guess I’m making some progress. It should be empty by the time I’m 80.

We moved here from Arizona in 2003, and (as usual) it took us literally years to unpack everything. Some stuff was not meant to be unpacked, really–I left my vinyl collection and 8″ reel-to-reel mix tapes in boxes on the big shelf in the mechanical room, knowing they’d be there if I needed them but not actually expecting to need them. (I admit, I’ve gone looking in the boxes for a vinyl album a couple of times.) But there’s one box on the high shelf here in my office, containing stuff that was in odd places in my Scottsdale office, stuff that I wasn’t really sure where to put or what to do with. Every so often I sift through the box for an hour or so, trashing some stuff and filing some stuff and putting the rest of it back in the box. It’s only about 1/4 full now, so I guess I’m making some progress. It should be empty by the time I’m 80.

This morning’s Wall Street Journal persuaded me that I am, for once, way ahead of the curve. The A-head story documents

This morning’s Wall Street Journal persuaded me that I am, for once, way ahead of the curve. The A-head story documents  I finally got a Millard Fillmore dollar at the bank today. I’ve been meaning to ask for one for a long time, but I hate to bother the poor tellers for silly things like that when there’s a line. Today, for whatever reason, the Wells Fargo branch at Safeway was empty and staffers were standing around BSing, so I asked. And I got.

I finally got a Millard Fillmore dollar at the bank today. I’ve been meaning to ask for one for a long time, but I hate to bother the poor tellers for silly things like that when there’s a line. Today, for whatever reason, the Wells Fargo branch at Safeway was empty and staffers were standing around BSing, so I asked. And I got.