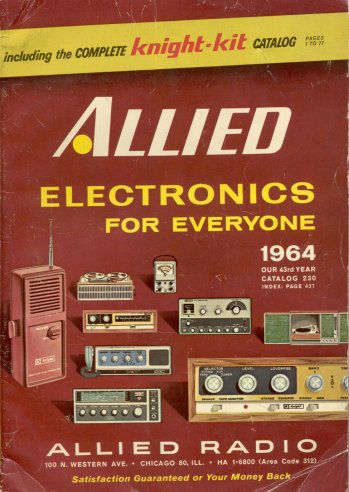

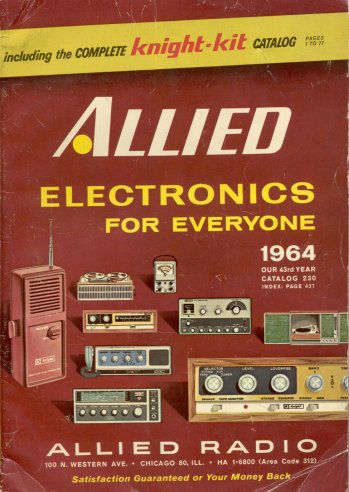

Harry Helms recently sent me something he thought I might enjoy: A copy of the 1964 Allied Radio catalog. When I opened the package and sat down with it, I realized that 1964 might well be my favorite year, if second to any then second only to the magical summer of 1969, when I met Carol. (1969 was painful at times for reasons that had nothing to do with Carol, first of which being that in 1964 my father was not dying of cancer.) I turned 12 in the summer of 1964, and had not yet begun to feel the hormone storm that would close in by the summer of '65 and make me crazy for years to come. Granted, many of the girls returned to IC School that September with a couple of things they didn't have the previous June, but apart from a passing fascination with a little girl named Laura that fall (which she never found out about—whew!) the whole girl thing blew past me. Halloween was on a Saturday that year—what luck!—and it was warm. Ten full hours to scavenge sugar from the neighbors, and we didn't need three sweaters under our costumes!

Harry Helms recently sent me something he thought I might enjoy: A copy of the 1964 Allied Radio catalog. When I opened the package and sat down with it, I realized that 1964 might well be my favorite year, if second to any then second only to the magical summer of 1969, when I met Carol. (1969 was painful at times for reasons that had nothing to do with Carol, first of which being that in 1964 my father was not dying of cancer.) I turned 12 in the summer of 1964, and had not yet begun to feel the hormone storm that would close in by the summer of '65 and make me crazy for years to come. Granted, many of the girls returned to IC School that September with a couple of things they didn't have the previous June, but apart from a passing fascination with a little girl named Laura that fall (which she never found out about—whew!) the whole girl thing blew past me. Halloween was on a Saturday that year—what luck!—and it was warm. Ten full hours to scavenge sugar from the neighbors, and we didn't need three sweaters under our costumes!

But for me in 1964, electronics was the thing. I had discovered electronics when I was 10, began seriously reading library books about it and building things when I was 11, and had begun to achieve some modest success by the time I turned 12. Simple radios were problematic, because my antenna looked right down the throat of hillbilly rock station WJJD's 50,000 watt directive array a mile or so northwest of me in Park Ridge, so I built other things: A two-transistor organ (with keys made of strips of tin can metal) a cigar-box intercom (put to good use by the Fox Patrol at Camp Owassipe that summer) and a capacity-operated proximity relay, which (being “spooky action at a distance”) was about as close to magic as it came.

That summer my father taught me how to take the CTA bus down to Six Corners (over my mother's strident objection) and always gave me a couple of dollars to spend at Olson Electronics on Milwaukee Avenue, back at a time when a couple of dollars would buy a pocketful of resistors, capacitors, and transistors. Allied was also in town (at 100 N. Western Avenue) but that was a lot farther away, and not in an especially good neighborhood. I knew Allied from its catalog and its catalog alone.

That summer my father taught me how to take the CTA bus down to Six Corners (over my mother's strident objection) and always gave me a couple of dollars to spend at Olson Electronics on Milwaukee Avenue, back at a time when a couple of dollars would buy a pocketful of resistors, capacitors, and transistors. Allied was also in town (at 100 N. Western Avenue) but that was a lot farther away, and not in an especially good neighborhood. I knew Allied from its catalog and its catalog alone.

But what a catalog! Anything a boy teetering on the edge of the Age of Lust might want was right there: Ham radio, CB, shortwave, hi-fi stereo, tape decks, portable radios, test equipment, speakers, tools, parts cabinets, resistors, capacitors, transformers, Miniboxes, plugs and sockets and chassis punches and antenna insulators, everything. The first 77 pages of the catalog was the full list of Knight Kits, which were cheaper than finished gear because you put them together yourself. I later went on to build a few a nd own many more Knight items, including the wonderful T-60 CW/AM transmitter, the nice LC-1 CPO, the so-so R-55A receiver, and the totally wretched T150A VFO transmitter, which wandered across more territory and with more brute persistence than an alley cat. Interestingly, the Knight Kit I wanted the most in 1964 I never got: The Span Master shortwave radio (at left) which I thought then (and may still) to be the coolest-looking radio in history.

nd own many more Knight items, including the wonderful T-60 CW/AM transmitter, the nice LC-1 CPO, the so-so R-55A receiver, and the totally wretched T150A VFO transmitter, which wandered across more territory and with more brute persistence than an alley cat. Interestingly, the Knight Kit I wanted the most in 1964 I never got: The Span Master shortwave radio (at left) which I thought then (and may still) to be the coolest-looking radio in history.

The back of the catalog was fascinating, as it listed in minuscule type endless small electronic parts and hardware, some of which I ordered through the mail, careful to send enough money to cover the goods and postage, and often (to be sure I hadn't messed up the shipping calculations) a little more—which Allied always honestly refunded, in the form of 4c and 7c credit slips to be applied to my next order. That part of the catalog is still useful as a reference: If you run across a Knight 61G466 power transformer at a hamfest, the catalog will tell you what the output voltages of its various windings are.

The back of the catalog was fascinating, as it listed in minuscule type endless small electronic parts and hardware, some of which I ordered through the mail, careful to send enough money to cover the goods and postage, and often (to be sure I hadn't messed up the shipping calculations) a little more—which Allied always honestly refunded, in the form of 4c and 7c credit slips to be applied to my next order. That part of the catalog is still useful as a reference: If you run across a Knight 61G466 power transformer at a hamfest, the catalog will tell you what the output voltages of its various windings are.

Some of the stuff I didn't want, and often had no clear concept of why it was useful: What good, after all, was a clock radio? I have an inner alarm clock that I can “set” to any arbitrary time and have never had any trouble bouncing out of bed at 6 ayem, often singing. (Carol is a very patient woman.) “You can wake up to music!” said the ad. Indeed. And you could plug your coffee pot into the back of the radio, which I just couldn't figure, as we were a gas household and an electric coffee pot was heresy, pure and simple. Tachometers and electronic ignition systems—no visceral response; when you're 12 and “small for your age” driving is almost unimaginable. The Blonder-Tongue (now there's a name for you!) TV mast signal amplifiers puzzled me; in Chicago you could practically get Channel 9 on your fillings. (You would, if WJJD hadn't already saturated them.)

1964 was the last great year of tube electronics, and the transmitters, receivers, and test gear units were not only big enough to see, they were big enough to cause serious injury if dropped on body parts. (I dropped a Central Electronics 100V transmitter on my thumb in 1998, and my thumbnail has never been the same since. And hey, in 1998 I was 46 and careful.) The prices on much of it were daunting: The Hallicrafters SR-150 SSB transmitter was $689—what the Inflation Calculator tells me would cost over $4600 today. The best a 12-year-old boy could do was look at the pictures and think, Hey, someday I may have this thing! The Allied catalog was the drool book of all drool books.

Yes, it was a great year. When my family went out to California on the Union Pacific that summer, my Allied catalog went with me (along with several issues of Popular Electronics and a couple of Alfred Morgan's books) and I got past the endless wheat fields of eastern Wyoming doodling chassis layouts on a pad of paper. That fall I built a regenerative receiver from a Popular Electronics article, with $15 worth of parts carefully ordered (and paid for by my saintly father) from the 1965 Allied catalog, which arrived without being summoned in October. I could never make it work well (though it picked up WJJD without any trouble) and there were times when I was tempted to give up electronics and just stare at Laura in English class like all the other guys did. But no: Girls were mysterious, and I would be years'n'years figuring them out. (I may still have a few years to go on that score.) But electronics? You flip a switch, and things happen. That was my kind of magic, and the Allied catalog was where it all came from, whether in grand dreams or grubby reality. I had both, and Halloween was on a Saturday! Life was good.

Harry Helms recently sent me something he thought I might enjoy: A copy of the 1964 Allied Radio catalog. When I opened the package and sat down with it, I realized that 1964 might well be my favorite year, if second to any then second only to the magical summer of 1969, when I met Carol. (1969 was painful at times for reasons that had nothing to do with Carol, first of which being that in 1964 my father was not dying of cancer.) I turned 12 in the summer of 1964, and had not yet begun to feel the hormone storm that would close in by the summer of '65 and make me crazy for years to come. Granted, many of the girls returned to IC School that September with a couple of things they didn't have the previous June, but apart from a passing fascination with a little girl named Laura that fall (which she never found out about—whew!) the whole girl thing blew past me. Halloween was on a Saturday that year—what luck!—and it was warm. Ten full hours to scavenge sugar from the neighbors, and we didn't need three sweaters under our costumes!

Harry Helms recently sent me something he thought I might enjoy: A copy of the 1964 Allied Radio catalog. When I opened the package and sat down with it, I realized that 1964 might well be my favorite year, if second to any then second only to the magical summer of 1969, when I met Carol. (1969 was painful at times for reasons that had nothing to do with Carol, first of which being that in 1964 my father was not dying of cancer.) I turned 12 in the summer of 1964, and had not yet begun to feel the hormone storm that would close in by the summer of '65 and make me crazy for years to come. Granted, many of the girls returned to IC School that September with a couple of things they didn't have the previous June, but apart from a passing fascination with a little girl named Laura that fall (which she never found out about—whew!) the whole girl thing blew past me. Halloween was on a Saturday that year—what luck!—and it was warm. Ten full hours to scavenge sugar from the neighbors, and we didn't need three sweaters under our costumes! That summer my father taught me how to take the CTA bus down to

That summer my father taught me how to take the CTA bus down to  nd own many more Knight items, including the wonderful T-60 CW/AM transmitter, the nice LC-1 CPO, the so-so R-55A receiver, and the totally wretched T150A VFO transmitter, which wandered across more territory and with more brute persistence than an alley cat. Interestingly, the Knight Kit I wanted the most in 1964 I never got: The Span Master shortwave radio (at left) which I thought then (and may still) to be the coolest-looking radio in history.

nd own many more Knight items, including the wonderful T-60 CW/AM transmitter, the nice LC-1 CPO, the so-so R-55A receiver, and the totally wretched T150A VFO transmitter, which wandered across more territory and with more brute persistence than an alley cat. Interestingly, the Knight Kit I wanted the most in 1964 I never got: The Span Master shortwave radio (at left) which I thought then (and may still) to be the coolest-looking radio in history. The back of the catalog was fascinating, as it listed in minuscule type endless small electronic parts and hardware, some of which I ordered through the mail, careful to send enough money to cover the goods and postage, and often (to be sure I hadn't messed up the shipping calculations) a little more—which Allied always honestly refunded, in the form of 4c and 7c credit slips to be applied to my next order. That part of the catalog is still useful as a reference: If you run across a Knight 61G466 power transformer at a hamfest, the catalog will tell you what the output voltages of its various windings are.

The back of the catalog was fascinating, as it listed in minuscule type endless small electronic parts and hardware, some of which I ordered through the mail, careful to send enough money to cover the goods and postage, and often (to be sure I hadn't messed up the shipping calculations) a little more—which Allied always honestly refunded, in the form of 4c and 7c credit slips to be applied to my next order. That part of the catalog is still useful as a reference: If you run across a Knight 61G466 power transformer at a hamfest, the catalog will tell you what the output voltages of its various windings are.