History is often written by the victors, and one of the gnarliest problems with victor history is not what the victors say, but what they leave out. You can ask the losers what they think, but sometimes what the victors leave out is something the losers would just as soon forget as well.

I learned something today about the founding of the Polish National Catholic Church, the first significant Old Catholic jurisdiction in America. The history we have of the PNCC describes the the tension between the predominantly Irish Roman Catholic clergy in America and the waves of dirt-poor Polish immigrants who started arriving in the late 1880s. This tension did exist and was the energizing force behind the Polish Old Catholic movement, but the actual triggering incident in the split between Polish immigrants and the Roman Catholic Church may have been a riot at St. Hedwig's Church in the Bucktown neighborhood of Chicago.

Some of the story is here; scroll down about a third of the way through the article. I'll summarize: Overwhelmed by the numbers of new immigrants pouring into Bucktown, the Polish-American pastor of St. Hedwig's brought in Fr. Anthony Kozlowski, a fiery, European-educated young Polish priest to help minister to the parishioners, few of whom spoke English. St. Hedwig's was under the administration of the Resurrectionists, an order of priests of mostly Polish extraction. Their former nationalities aside, the Resurrectionists were conservative and fiercely loyal to the Pope. The order attempted to play down the Polishness of religious expression at St. Hedwig's. Many of the younger immigrants were suspicious of the order, thinking that it was being pressured by the Irish hierarchy that otherwise ran the American church, and the Chicago church in particular. Details are thin, but in early 1895, Kozlowski led a revolt against the Resurrectionist pastor, Thaddeus Barzynski, and his brother Joseph Barzynski, that eventually resulted in two-thirds of the St. Hedwig's congregation quitting the church and following Kozlowski away from governance by the Pope.

The revolt went critical on February 7, 1895. Kozlowski's hotheads broke into the St. Hedwig's rectory, where the Barzynskis had barricaded themselves, and assaulted the priests. The police were called, and found a crowd of 3,000 immigrants milling around the church. When the officers attempted to disperse the crowd, several protesters threw powdered red pepper in their faces. Dozens were injured in the ensuing brawl, and Chicago's (Irish) Roman Catholic archbishop shut down St. Hedwig's for several months.

By that time, the 1,000 or so immigrants who objected to Papal rule had bought land a few blocks away and began built their own church, All Saints Cathedral. This is where my other histories pick up: Kozlowski traveled to Berne, where he had earlier met the the leaders of the European Old Catholic Church. The Old Catholic bishops of Germany, Switzerland, and Holland consecrated him as the first bishop of the Polish Catholic Church of America. A similar but unrelated situation was then playing out in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in which a parish priest named Francis Hodur broke with the Pope and in 1897 founded the Polish National Independent Catholic Church, again outside Papal control. Still more Polish-American groups broke with the Pope as the 1890s wound down, including a major one in Buffalo and smaller ones in Cleveland and other cities. In the years after Kozlowski died unexpectedly in 1897, the European Old Catholics persuaded the various American parishes of independent Polish Catholics to unite under a new banner, the Polish National Catholic Church. In 1907 Hodur was consecrated bishop by the same groups that had consecrated Kozlowski, and he led the PNCC throughout his long life until his death in 1953.

It's interesting to see where the various histories disagree: The current Roman Catholic pastor of St. Hedwig's of Chicago provided the factual information on Kozlowski's revolt that I summarized above, but suggested that the Polish National Catholic Church never really went anywhere. Not so: The PNCC was a force in American Catholicism as long as there were Polish-speaking communities in America, and only began to decline after the children of Polish immigrants assimilated into English-speaking American culture after WWII. (There has been a resurgence of PNCC parishes in Wisconsin and other places in the past few years, serving recent Polish immigrants.) Histories of the PNCC emphasize the heroic efforts of Bishop Hodur, even though Kozlowski was the first Polish American Catholic to quit the Roman church, and made the European Old Catholics aware of Polish discontent with Papal Catholicism. Riots of Poles against the Roman Catholic Church happened in other cities as well as Chicago, but PNCC histories tiptoe very lightly around them. Histories of the PNCC published by the PNCC mention Kozlowski only in passing, if they mention him at all.

Once again, the lesson is this: If you want anything approaching the truth, you have to listen to both sides. And sometimes, you have to fill in the gaps that neither side wishes to fill. But hey, who ever said history was an easy subject?

Somewhere in Chicago (Pete Albrecht and I are still trying to figure out precisely where) there was once a very Gothic-looking building with a giant turtle on top of it. It was the Turtle Wax turtle, of course, and it existed when I was quite young. Any time we'd be in the car passing by it, my folks would very carefully point it out. That would have been 1958-1962 or so. Pete thinks the building is the Wendell Bank Building at the intersection of Madison, Ashland, and Ogden, and it certainly looks right, though Pete remembers the sign being somewhere on Cicero and not Ashland. I confess that I have no idea, but that intersection would have been on the way to visit my grandfather and Uncle Louie, so it's a plausble hypothesis.

Somewhere in Chicago (Pete Albrecht and I are still trying to figure out precisely where) there was once a very Gothic-looking building with a giant turtle on top of it. It was the Turtle Wax turtle, of course, and it existed when I was quite young. Any time we'd be in the car passing by it, my folks would very carefully point it out. That would have been 1958-1962 or so. Pete thinks the building is the Wendell Bank Building at the intersection of Madison, Ashland, and Ogden, and it certainly looks right, though Pete remembers the sign being somewhere on Cicero and not Ashland. I confess that I have no idea, but that intersection would have been on the way to visit my grandfather and Uncle Louie, so it's a plausble hypothesis. The search for the abode of the Really Big Turtle did turn up an interesting little video on

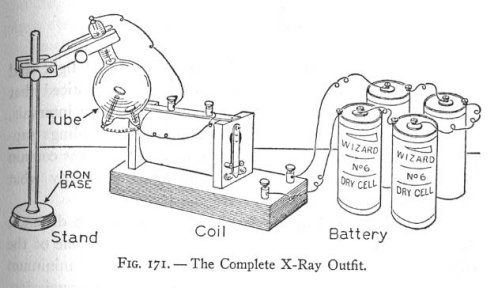

The search for the abode of the Really Big Turtle did turn up an interesting little video on  It took a few minutes of flipping through some books in my workshop, but I eventually found what I remembered: That one of my “boys” books contained a description of a tabletop X-ray setup. The book in question is The Boy Electrician, the first volume of many from Alfred Morgan, who later wrote The Boys' First Book of Radio and Electronics and its three sequels, all of which loomed large in my tinkersome youth. The Boy Electrician was originally published in 1913 and is now in the public domain. The 1913 edition has been reprinted by Lindsay Books and I consider it worth having. There was a significant revision in 1943 that added chapters on radio and a few other things, and as best I can tell, the copyright on that edition was not renewed and it too is now in the public domain. A 40 MB PDF of the 1943 edition is

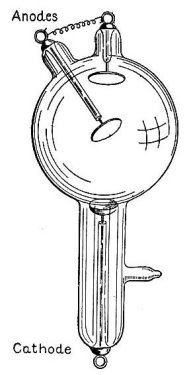

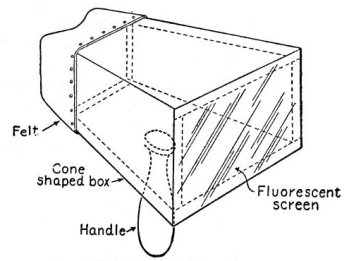

It took a few minutes of flipping through some books in my workshop, but I eventually found what I remembered: That one of my “boys” books contained a description of a tabletop X-ray setup. The book in question is The Boy Electrician, the first volume of many from Alfred Morgan, who later wrote The Boys' First Book of Radio and Electronics and its three sequels, all of which loomed large in my tinkersome youth. The Boy Electrician was originally published in 1913 and is now in the public domain. The 1913 edition has been reprinted by Lindsay Books and I consider it worth having. There was a significant revision in 1943 that added chapters on radio and a few other things, and as best I can tell, the copyright on that edition was not renewed and it too is now in the public domain. A 40 MB PDF of the 1943 edition is  Morgan explains that you can either view images directly with a fluoroscope or expose ordinary photographic plates by placing an object to be X-rayed between the tube and the plate and leaving it there for fifteen minutes. This includes things like purses, mice, or…your hand. If you have the money, he also explains that a hand-held fluoroscope may be constructed by simply coating a sheet of white paper with crystals of platinum barium cyanide. It looks like the fluoroscope screen is used by basically staring at the X-ray tube with the object to be X-rayed between the tube and the paper screen.

Morgan explains that you can either view images directly with a fluoroscope or expose ordinary photographic plates by placing an object to be X-rayed between the tube and the plate and leaving it there for fifteen minutes. This includes things like purses, mice, or…your hand. If you have the money, he also explains that a hand-held fluoroscope may be constructed by simply coating a sheet of white paper with crystals of platinum barium cyanide. It looks like the fluoroscope screen is used by basically staring at the X-ray tube with the object to be X-rayed between the tube and the paper screen. It would be interesting to know just how many boys bought the tube and tried to make it work; though given that $4.50 in 1913 would be about $100 today, I doubt it was many. Nor do I know how toxic platinum barium cyanide is, but I'm guessing a little more than iron filings. (On the other hand, my 1962 chemistry set contained a little bottle of sodium ferrocyanide, which sounds much worse than it actually is.)

It would be interesting to know just how many boys bought the tube and tried to make it work; though given that $4.50 in 1913 would be about $100 today, I doubt it was many. Nor do I know how toxic platinum barium cyanide is, but I'm guessing a little more than iron filings. (On the other hand, my 1962 chemistry set contained a little bottle of sodium ferrocyanide, which sounds much worse than it actually is.) Just got back from Chicago and there's way too much to do (and I have a six-hour dental appointment scheduled for Thursday!) but I did want to report on something I saw on our trip that I haven't seen for a very long time: A shoe-fitter X-ray machine. People my age or older may remember going to a shoe store in the 1950s or earlier, and having your parents and the shoe store man look at your feet inside a new pair of shoes to make sure they fit correctly. I know I did this, and I vaguely remember the humming machine, but I suspect I was just too short to get to look into the machine myself. (I doubt I would forget a real-time X-ray image of my own bones. Urrrrp…)

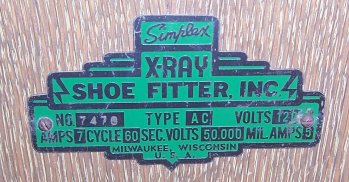

Just got back from Chicago and there's way too much to do (and I have a six-hour dental appointment scheduled for Thursday!) but I did want to report on something I saw on our trip that I haven't seen for a very long time: A shoe-fitter X-ray machine. People my age or older may remember going to a shoe store in the 1950s or earlier, and having your parents and the shoe store man look at your feet inside a new pair of shoes to make sure they fit correctly. I know I did this, and I vaguely remember the humming machine, but I suspect I was just too short to get to look into the machine myself. (I doubt I would forget a real-time X-ray image of my own bones. Urrrrp…) plate (below) indicates that the power supply drew 7 amps and put out 50,000 volts at 5 milliamps. That kind of power will generate considerable radiation out of an X-ray tube, and the associated hazards eventually put an end to continuous-beam fluoroscopy by untrained operators, in shoe stores and elsewhere. The hazards appeared not so much to the occasional shoe store customer as to the sales reps who ran the machines and sometimes to professional shoe models who tested shoes for manufacturers using machines like this; one woman's foot was damaged so badly in testing shoes that it had to be amputated.

plate (below) indicates that the power supply drew 7 amps and put out 50,000 volts at 5 milliamps. That kind of power will generate considerable radiation out of an X-ray tube, and the associated hazards eventually put an end to continuous-beam fluoroscopy by untrained operators, in shoe stores and elsewhere. The hazards appeared not so much to the occasional shoe store customer as to the sales reps who ran the machines and sometimes to professional shoe models who tested shoes for manufacturers using machines like this; one woman's foot was damaged so badly in testing shoes that it had to be amputated.