My miscellaneous low-priority do-it list has gotten mighty long since January, and every so often I set aside some time to knock off a few items. This morning something interesting bubbled up to the top of the stack: Claim my books under the Google Books Settlement. I’ve known about this for quite some time and haven’t had the mental bandwidth to look into it deeply, but having been roused by rowdy dogs this morning a little earlier than I’d like, I sat down here and read the material.

I’m not quite sure what to think. Google is helping to create a registry of old books that are still in copyright but no longer in print. This is a very good thing, and I signed up to support that effort if nothing else. What Google intends to do is create a legal framework for making those old books available as paid ebooks, and give authors (and where publishers still have rights, publishers) a portion of the take. Google has already scanned a great many books, including a few of my own, and if I can pick up a few quarters by buying in to the system, I will. (Alas, I doubt my 1987 work Turbo Pascal Solutions is going to be a hot seller.)

Mostly, I want the problem of orphan books to be finessed, and I want it finessed without Big Media’s copyright lobby shaping it so that it routes all the money to them and leaves the rest of us penniless in the dust. People gripe about Google’s interest in the whole thing–they could make an enormous amount of money here if this thing catches on, and in essence become the planet’s largest publisher–but the idea is sound and Google may be the best that we can do.

If anyone has any interest in this, go to the Google Books Settlement Site and read the sizeable FAQ. I especially encourage any of my author friends who have published books to decide what they think about the whole thing, and either sign in or opt out. Signing up can be done until January 5, 2010, but opting out must be done by May 5, 2009. I’m guessing that popular authors and their heirs will opt out, figuring they may be able to get a better deal somewhere, and the great starving writer masses (who know that there are no deals on their horizon) will sign on. And that’s actually a good thing: The great starving writer masses deserve a way to get whatever scraps may fall from the ebooks publishing table, as the publishing industry generally becomes more and more of a “winner takes all” kind of business.

The framework has not yet been completely created, but it’ll happen over time, and it will be very interesting to see if anything comes of it long-term. I’m watching the whole business closely and will report here from time to time, especially once I finish the Book That Ate 2009.

As I mentioned yesterday, my publisher wants me to revise Assembly Language Step By Step over the coming year, for release in early 2010. I had assumed for some time that they considered the book a dead issue, though judging by my royalty statements, it continues to sell. And that's a clue: When the market is bad, publishers get nervous about striking out in entirely new directions with new series and lots of new titles. A handful of books are what they call “evergreens,” because they sell all year, every year, for years and years and years. I think that a lot of evergreen titles are going to be freshened up and reissued in the next few years. The publisher considers my book an evergreen (it was first published, after all, in 1989, and has sold steadily ever since) and the acquisitions editor had done her homework. She wanted DOS to go. She wanted to ditch the CD bound into the book. She wanted more Linux coverage. And if possible, she wanted me to use Ubuntu as the flavor of Linux cited in the book.

As I mentioned yesterday, my publisher wants me to revise Assembly Language Step By Step over the coming year, for release in early 2010. I had assumed for some time that they considered the book a dead issue, though judging by my royalty statements, it continues to sell. And that's a clue: When the market is bad, publishers get nervous about striking out in entirely new directions with new series and lots of new titles. A handful of books are what they call “evergreens,” because they sell all year, every year, for years and years and years. I think that a lot of evergreen titles are going to be freshened up and reissued in the next few years. The publisher considers my book an evergreen (it was first published, after all, in 1989, and has sold steadily ever since) and the acquisitions editor had done her homework. She wanted DOS to go. She wanted to ditch the CD bound into the book. She wanted more Linux coverage. And if possible, she wanted me to use Ubuntu as the flavor of Linux cited in the book. terms. I kept flipping into a wonderful DK book called The Visual Dictionary of Buildings to clarify certain elements of church architecture. Now that book I recommend, especially if you’re a writer trying to set a scene in a complicated building and aren’t entirely sure what an oculus is. (Or—quick, now!—define a “spandrel”.) There are some factual errors in Basilica, one of the worst of which suggests that poured concrete was used in some places in St. Peter’s. Not so—poured concrete was an ancient technology that was lost after Imperial Rome came apart and was not recovered until the 19th Century, or pretty close to it. St. Peter’s was built almost entirely of mortared masonry and sculpted stone.

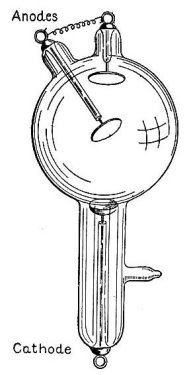

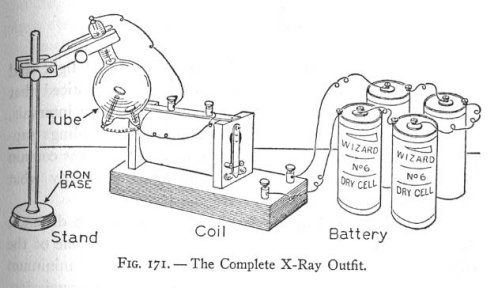

terms. I kept flipping into a wonderful DK book called The Visual Dictionary of Buildings to clarify certain elements of church architecture. Now that book I recommend, especially if you’re a writer trying to set a scene in a complicated building and aren’t entirely sure what an oculus is. (Or—quick, now!—define a “spandrel”.) There are some factual errors in Basilica, one of the worst of which suggests that poured concrete was used in some places in St. Peter’s. Not so—poured concrete was an ancient technology that was lost after Imperial Rome came apart and was not recovered until the 19th Century, or pretty close to it. St. Peter’s was built almost entirely of mortared masonry and sculpted stone. It took a few minutes of flipping through some books in my workshop, but I eventually found what I remembered: That one of my “boys” books contained a description of a tabletop X-ray setup. The book in question is The Boy Electrician, the first volume of many from Alfred Morgan, who later wrote The Boys' First Book of Radio and Electronics and its three sequels, all of which loomed large in my tinkersome youth. The Boy Electrician was originally published in 1913 and is now in the public domain. The 1913 edition has been reprinted by Lindsay Books and I consider it worth having. There was a significant revision in 1943 that added chapters on radio and a few other things, and as best I can tell, the copyright on that edition was not renewed and it too is now in the public domain. A 40 MB PDF of the 1943 edition is

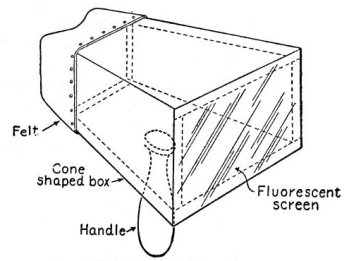

It took a few minutes of flipping through some books in my workshop, but I eventually found what I remembered: That one of my “boys” books contained a description of a tabletop X-ray setup. The book in question is The Boy Electrician, the first volume of many from Alfred Morgan, who later wrote The Boys' First Book of Radio and Electronics and its three sequels, all of which loomed large in my tinkersome youth. The Boy Electrician was originally published in 1913 and is now in the public domain. The 1913 edition has been reprinted by Lindsay Books and I consider it worth having. There was a significant revision in 1943 that added chapters on radio and a few other things, and as best I can tell, the copyright on that edition was not renewed and it too is now in the public domain. A 40 MB PDF of the 1943 edition is  Morgan explains that you can either view images directly with a fluoroscope or expose ordinary photographic plates by placing an object to be X-rayed between the tube and the plate and leaving it there for fifteen minutes. This includes things like purses, mice, or…your hand. If you have the money, he also explains that a hand-held fluoroscope may be constructed by simply coating a sheet of white paper with crystals of platinum barium cyanide. It looks like the fluoroscope screen is used by basically staring at the X-ray tube with the object to be X-rayed between the tube and the paper screen.

Morgan explains that you can either view images directly with a fluoroscope or expose ordinary photographic plates by placing an object to be X-rayed between the tube and the plate and leaving it there for fifteen minutes. This includes things like purses, mice, or…your hand. If you have the money, he also explains that a hand-held fluoroscope may be constructed by simply coating a sheet of white paper with crystals of platinum barium cyanide. It looks like the fluoroscope screen is used by basically staring at the X-ray tube with the object to be X-rayed between the tube and the paper screen. It would be interesting to know just how many boys bought the tube and tried to make it work; though given that $4.50 in 1913 would be about $100 today, I doubt it was many. Nor do I know how toxic platinum barium cyanide is, but I'm guessing a little more than iron filings. (On the other hand, my 1962 chemistry set contained a little bottle of sodium ferrocyanide, which sounds much worse than it actually is.)

It would be interesting to know just how many boys bought the tube and tried to make it work; though given that $4.50 in 1913 would be about $100 today, I doubt it was many. Nor do I know how toxic platinum barium cyanide is, but I'm guessing a little more than iron filings. (On the other hand, my 1962 chemistry set contained a little bottle of sodium ferrocyanide, which sounds much worse than it actually is.)